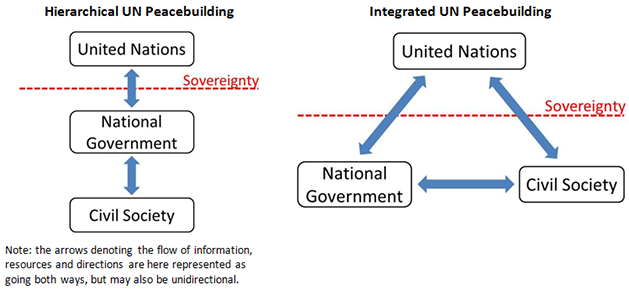

Just before the holidays, Tim Donais and I travelled to New York to interview UN officials and other relevant experts on the institutional architecture of UN peacebuilding. These discussions helped refine our inquiry into vertically integrated peacebuilding by distinguishing two possible modes of UN peacebuilding – hierarchical and integrated – which are represented graphically then compared below. Our central research question may thus be articulated: what are the opportunities, obstacles, merits and limitations of a shift from the hierarchical mode to an integrated mode of UN peacebuilding? The hierarchical mode represents the orthodox UN approach, whereas the integrated mode represents the possibility of a vertically integrated form of peacebuilding that engages both state and society. While these two modes are presented here as ideal types, in practice they mark the opposite ends of a spectrum and any present or future UN peacebuilding mission likely lies somewhere in between.

The integrated mode raises numerous difficulties, especially insofar as it pushes the institutional limitations of the UN and intrudes on domestic politics. Given the scale of these challenges, why consider the integrated mode at all?

The main reason is that the hierarchical mode excludes the majority of citizens from the peacebuilding process, and any peacebuilding process that goes no further than ‘elite agreement’ rests on unstable foundations. Indeed, the discourse on liberal peacebuilding has already moved towards deeper civil society engagement as a critical way forward even if UN practice yet lacks the innovations necessary to implement these directions in practice.

The hierarchical mode of peacebuilding focuses on what we might call the ‘first peace’. It stems from the peace agreement negotiated between the government and rebel faction, and seeks to construct institutions that balance the interests of these formerly warring factions so that they do not revert to armed conflict. The first peace, however, is a bargain amongst elites that excludes the rest of society (which has generally suffered the brunt of the war).

The integrated mode of peacebuilding seeks to construct a ‘second peace’ by ensuring that that new political arrangements adequately incorporate the needs, interests and aspirations of society more broadly. The first peace prevents the recurrence of the armed conflict that has just ended; the second peace aims to create the arrangements and processes that address the drivers of violence and conflict to prevent new and other forms of mass violence from erupting [3]. It pursues this aim through the (re-) negotiation of a broad, peaceful and inclusive social contract. It aspires to peaceful politics that can grapple with new potentials for mass violence, rather than just resolving the most recent manifestation, and does so by directly including civil society in governance.

While the first peace demands a focus on building strong national institutions that effectively balance elite interests, the second peace is more concerned with the inclusion and participation of citizens in the governing process. The latter focus is reflected in a shift in the discourse on statebuilding from state institutions to state-society relations. As the OECD-DAC argues, “Statebuilding must be understood in the context of state-society relations; the evolution of a state’s relationship with society is at the heart of statebuilding” (2011: 11). The shift reflects the shortcomings of the hierarchical mode to produce the character of peace sought by both international peacebuilders and everyday citizens.

Michael Barnett and Christoph Zürcher’s (2009) account of the ‘peacebuilder’s contract’ helps explain why the hierarchical mode of peacebuilding often fails to achieve its liberal aspirations. International peacebuilders generally start by seeking deep social change and a positive peace, but are simultaneously committed to achieve national ownership of the process. State elites have their own interests in maintaining power and survival but desire the resources and legitimization provided by international peacebuilding programs. The ensuing negotiation between the two produces ‘compromised peacebuilding’ in which national elites accede to international peacebuilding in exchange for resources, but their commitment to liberalization remains largely symbolic. Subnational elites, who are critical to stability, want to maintain their autonomy and thus fear peacebuilding programs that might transform power structures and expand state control into the periphery. Because the state must somehow co-opt these elites, the transformative elements of peacebuilding are further diluted in the negotiation between state elites and subnational elites. The resulting contract achieves stability (which all three classes of actors desire), resource flows to elites, and the symbolic endorsement of liberalism (the national ownership peacebuilders seek), but at the expense of liberalization and the transformation of politics (which state and subnational elites resist in order to defend their power and interests).

This ‘contract’ helps to explain why “liberal peacebuilding is more likely to reproduce than to transform existing state-society relations and patrimonial politics” (Barnett and Zürcher, 2009: 36). Peacebuilding may be able to expand the ‘degree of state’ (and thus stability) but does little to transform the ‘kind of state’ that would mark a change between pre-war, wartime and post-war politics (25). It can strengthen state institutions, but does much less to improve state-society relations. Compromised peacebuilding, however, “if done right, might be the best of all possible worlds” (49), especially if the models behind liberal peacebuilding are not universally applicable, possible or desirable. “The only way out,” Barnett and Zürcher posit, “is for peacebuilders to confess a high degree of uncertainty—and actively incorporate local voices into the planning process” (48). The integrative mode offers one possibility for doing so in that it aims to empower civil society as a more transformative counterweight to conservative elites and power structures.

Of course, the integrated mode of peacebuilding deeply involves the UN in the domestic politics of the host nation and challenges traditional notions of sovereignty. This challenge relates to two important yet contradictory critiques of liberal peacebuilding. As Roland Paris explains:

“On one hand… [international peacebuilders] were under pressure to expand the scope and duration of operations in order to build functioning and effective governmental institutions in war-torn states, and to avoid problems of incomplete reform and premature departure seen in East Timor and elsewhere. On the other hand, they were also under pressure to reduce the level of international intrusion in the domestic political process of the host states. Achieving the first goal seemed to require a relatively ‘heavy footprint’, or a large and long-term international presence with extensive powers, particularly in cases where governmental institutions are dysfunctional or non-existent; whereas the second goal seemed to require a relatively ‘light footprint’, a small and unobtrusive presence that would maximise the freedom of local actors to pursue their own peacebuilding goals. Squaring these two objectives became – and remains today – a crucial conceptual and strategic challenge for practitioners. Simply put, if both the heavy footprint and the light footprint are problematic, what is the ‘right’ footprint?” (2010: 343).

The integrated mode of peacebuilding offers a potential ‘right’ footprint by emphasizing popular sovereignty rather than government sovereignty. It would employ a heavy footprint to bring civil society into governance rather than dealing exclusively with elites and governmental institutions, and thus maintain the normative ideal of sovereignty as the ability of a society to determine its own destiny. Along these lines, Paris concludes that “more research is needed on the sources of local legitimacy in peacebuilding, including the challenge of incorporating mass publics and non-elites into post-conflict and political and economic structures and directly into the management of international peacebuilding operations themselves” (2010: 356-7).

Given these critical perspectives on traditional UN peacebuilding and calls for greater civil society engagement, the potential and possibility of integrated peacebuilding are immensely timely and pertinent questions. Ultimately, by distinguishing these two ideal-type modes of UN peacebuilding, we can ask the following research questions:

- What does the Sierra Leone experience tell us about the merits and challenges of each mode?

- To what extent is the hierarchical mode insufficient and the integrated mode necessary for peacebuilding success?

- To what extent is civil society engagement and popular inclusion necessary for successful peacebuilding?

- What are the institutional obstacles that impede the UN from adopting the integrated mode?

[1] Note that these ‘aims’ are also different definitions of statebuilding, and may even be considered rival conceptions of peacebuilding.

[2] The UN Peacebuilding Commission is mandated to bring together “all relevant actors” in peacebuilding, but these actors are not specified.

[3] Importantly, the second peace may not remove the structural causes of conflict, but rather develop procedures and expectations that can deal with these causes peacefully, keeping them from erupting in violence (though ideally it creates arrangements that can gradually reduce and eliminate root causes of conflict).

References:

Michael Barnett and Christoph Zürcher (2009). “The Peacebuilder’s Contract: How External Statebuilding Reinforces Weak Statehood,” in The Dilemmas of Statebuilding: Confronting the Contradictions of Postwar Peace Operations edited by Roland Paris and Timothy D. Sisk. London and New York: Routledge. Pages 23-52.

OECD-DAC (2011). Supporting Statebuilding in Situations of Conflict and Fragility: Policy Guidance. OECD Publishing. Available at: www.gpplatform.ch/sites/default/files/OECD%20Policy%20Guidance_1.pdf

Paris, Roland (2010). “Saving Liberal Peacebuilding,” Review of International Studies vol. 36 no. 2. Pages 337-365.