Those of us who have worked on conflict know the dangers of a breakdown of the social compact between state and society: instability, ethnic or religious discrimination, and a descent into violence. In extreme cases, governments become the agents of gross human rights abuses to their citizenry, as in Cambodia, Rwanda, Darfur and Syria. In the 1990s and 2000s, the United Nations led the international community to recognize that when a government is unable or fails to provide security for its citizens, the international community has a responsibility to act. We moved the concept of security beyond the state to embrace individuals, peoples and groups.

These developments are universal and they have direct relevance to the peace and security of Africa. The African continent has made important progress — political and economic — in recent decades, but some countries remain in the throes of violent conflict, while others are prone to relapses. As a result, Africa continues to host a majority of UN blue helmets. What has changed, however, is that African states themselves are playing a bigger role in their own collective security. The African Union has developed an impressive set of institutions to prevent, manage and resolve conflict, including early warning capacity.

These African solutions must also reach beyond the state. Soon after stepping down as UN Secretary-General, I worked to help organize a multi-stakeholder effort in the Kenyan electoral crisis of 2007-2008. It is not an exaggeration to recognize that the strength of Kenyan civil society institutions helped to bring the country back from the brink.

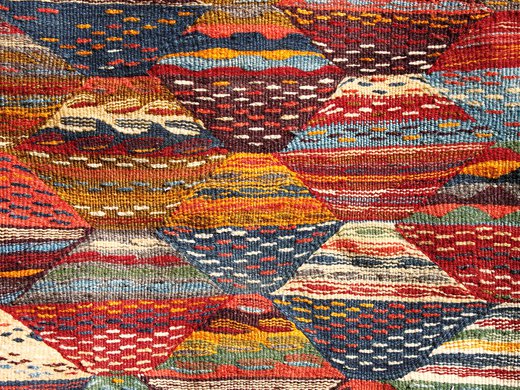

This brings me to the book The Fabric of Peace in Africa: Looking beyond the State that addresses the societal environment of conflict and the potential contribution to managing conflict of a wide range of social groups and institutions. These studies, edited and framed by scholar-practitioners Chester A. Crocker and Pamela Aall, bring together leading African and external experts who make a significant contribution to our understanding of the challenges and possibilities of African efforts to build sustainable peace and security. The volume shines a light on the role that individuals, groups and social institutions play in peace and conflict.

The authors in the book delve into topics ranging from religion and education policy to migration and youth engagement in order to understand how these groups and organizations affect social attitudes and proclivities toward violence and peace. It is clear from this examination that all those institutions that respond to conflict — the United Nations, the African Union, the sub-regional organizations and non-government organizations — need to reach out beyond the state in order to build a firm foundation for peace. The book is a rewarding mosaic that looks at Africa’s conflict challenges from the inside as well as the outside, and helps us understand the complexities of building peace and building equitable, accountable and inclusive societies.

This article is excerpted from a foreword to the book The Fabric of Peace in Africa: Looking beyond the State, edited by Pamela Aall and Chester A. Crocker.