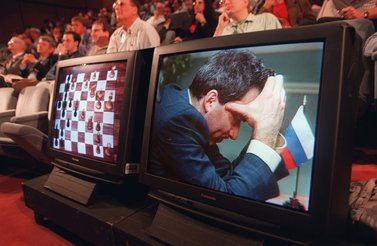

On December 19, 2019, The New York Times’ Privacy Project published its first article in a series on the sensitivity of location data, starting with an article about nearly 50 billion data points associated with 12 million Americans that are available through commercial brokers. One of the most interesting aspects of the article, though, is that it’s not reporting on the availability of location data — that’s been well-covered — rather, the piece focuses on what can be done with location data.

The New York Times’ series is reminiscent of another location data story from early 2018, when a high school student used the location data and maps openly published by Strava, an exercise tracking app, to identify American military facilities abroad. The news wasn’t that Strava collected or published location data, it’s that no one seemed to understand how much risk could come from publishing location data. The risks posed by location data aren’t new, nor are the concerns raised in a range of industries: I, for example, raised the legal problems caused by using mobile phone location data in the response to the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Our public and collective understanding of how data can and is being used against us, however, is a critical catalyst for public and governmental response.

The growing controversy around the sensitivity of location data highlights a larger issue: the digital contracts we sign with a variety of service providers don’t protect us from the harms caused by the use of data. One major reason for that is the disappearance of a critical part of any commercial transaction: the warranty.

A warranty is a guarantee that a company makes, which usually says that its product, when used in a specific context or way, will perform its function to a particular standard. So, for example, car manufacturers guarantee their cars for driving on roads, but not for driving underwater. And, because of that, if you drive your car underwater and it breaks down, or causes harm, you can’t hold the manufacturer liable. If manufacturers didn’t specifically issue warranties for their cars, they could, theoretically, be sued for damages related to an even wider range of misuses and harms. So, warranties don’t just create liability, they focus it: warrantied products face specific liability, whereas products without a warranty face broad, less predictable liability.

Warranties do two critical things. First, they require a manufacturer to specify how and where its product should be used and to run tests to ensure it performs under these conditions. And second, warranties attach liability to the risks created by a product to the user. Warranties are familiar enough to seem trivial, but they are an important part of how we structure the responsibility for the things we create, share and sell — including intangible and digital products.

In analog products, warranties are often regarded as badges of quality; companies that are willing to guarantee their products are seen as more reliable than those that do not. Those guarantees didn’t come to be for marketing’s sake alone. Companies, especially those working on products with significant or potentially dangerous impacts, would go through the effort of defining and testing not only whether a product worked but what conditions it worked in and how it worked in different use cases. In short, to offer a warranty, companies needed to do extensive contextual research and development before launching the product at all.

Of course, the warranty, in some ways, protects consumers. But largely, warranties are meant to protect companies from liability associated with incorrect, unsafe or unethical use of their products. By accepting liability for a specific set of uses, companies also shield themselves from liability for nearly every other kind of use.

The trade-off, though, for open-ended digital licensing is that it severs the connections between the links of a digital supply chain. On one hand, that means that data and code are available — often for free and without any contractual relationship at all. On the other hand, without a coherent supply chain, made of individual links capable of guaranteeing their individual quality, it’s also nearly impossible to enforce the protections that prevent abuse. Unfortunately, the trend away from warranties spread well beyond the public interest or openly licensed products and is now the norm for digital contracting.

Those norms apply to our most vital services — including the mobile phone and internet service providers who are reselling our most sensitive data, such as location data, to third party brokers for indiscriminate reuse.

Companies that produce digital products, like software and data, and especially those that provide digital infrastructure, like mobile network operators, should be required to warranty not only their products, but how those products are meant to be used. For example, there are companies that produce machine learning tools to analyze the way that people walk. Walking signatures are pretty identifying information — and they can be used to detect a wide range of health conditions, and some companies even suggest they can indicate whether a person is hiding something. Here, the company developing the machine learning tool could warranty that the tool is fit for a specific use, like helping people identify the right sneaker or to diagnose chronic pain. The effect of that warranty is to help hold the company to a high standard for those use cases, but also to ensure that if someone repurposes their service in a way they didn't anticipate — like to identify sexual orientation or security threats — they aren't held accountable for the unreasonable and unpredictable harms that result from intentional misuse.

If we’re serious about building a digital future that we can rely on, we should start by requiring companies to provide warranties for digital services — and not only for their services, but for the ways they data is used and shared writ large. The impact of digital and data products, like analog products, isn’t unknowable, it’s contextual. And, just like we used to, we should support companies willing to accept responsibility for the impact of their services. Because right now, the future is not warrantied. And, until it is, we’ll continue to get surprised by the inventive ways that the digital world can be leveraged against us.