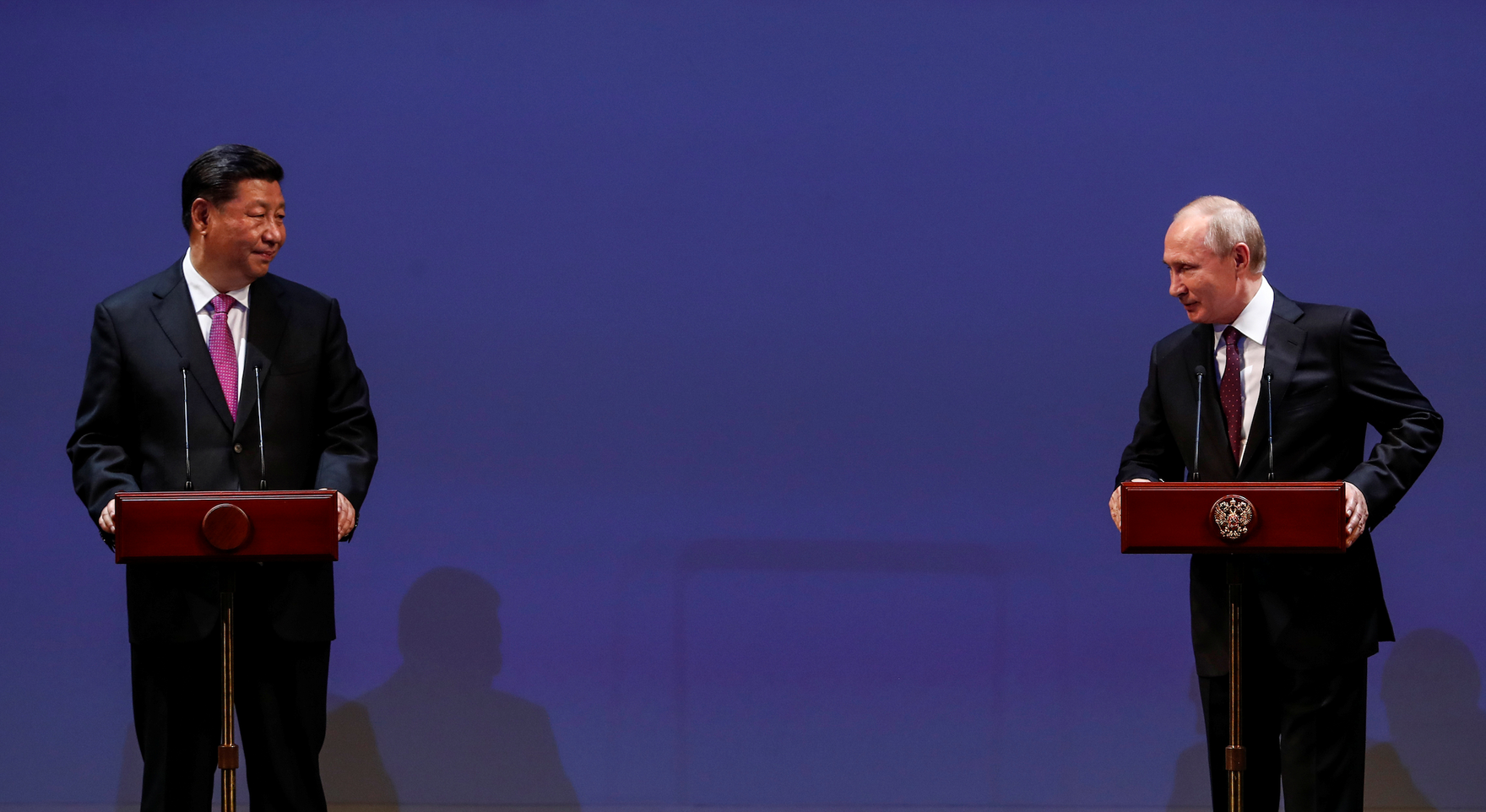

While speaking about cyberspace threats in March 2019, US National Security Agency senior adviser Rob Joyce noted that he viewed Russia as a “hurricane” and the People’s Republic of China as “climate change.” Joyce argued Russia is often disruptive, whereas China is “long, slow, pervasive.” In late 2020, MI5 Director General Ken McCallum similarly characterized Russia’s behaviour as “bursts of bad weather” while noting “China is changing the climate.”

It’s prudent to revisit these comments now. While Russian leadership overall appears to favour more “direct” approaches to furthering its interests, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems committed to indirectly (and in some cases, covertly) reshaping international norms and institutions to better suit the politburo’s preferences.

Both countries pose challenges to the international system. However, China’s slow reshaping of the liberal international order to benefit its political regime, domestic enterprises (such as Huawei) and industry poses the greatest challenge to Canada’s interests.

Short-Term Disruptions, Long-Term Shifts

Russia’s foreign policy has in the past been strategic and restrained. However, Russia’s behaviour in the international system in recent years, particularly this year, resembles a violent storm. Russian foreign policy is often assertive,quantifiable and impactful.

Liberal democracies also seem to react to Russia’s behaviour as many of us would to violent bad weather — that is, with immediate concern, and a desire to batten the hatches and initiate countermeasures.

Partners came together and reacted quickly to the all-out Russian invasion of Ukraine, for example, using international organizations such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Group of Seven and even the United Nations to good effect. Russia’s earlier brazen attack on former Russian intelligence official Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia Skripal in 2018 also prompted a strong response from UK allies, many of whom ordered the expulsion of several suspected Russian spies.

China’s behaviour in the international system, in contrast, has not historically elicited the same level of broad and unified concern. This, despite the fact China has repeatedly proven it can be provocative and aggressive, as, for example, in its imprisonment of Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor, island building in the South China Sea, elimination of democracy in Hong Kong and perpetual harassment of Taiwan.

And, as with climate change, some dismiss the long-term impacts of China’s actions, even though the country has shown the potential to have a destabilizing impact on the twenty-first century’s international order.

This apathy is partly due to China’s ability to manipulate and reshape international organizations to legitimize its behaviour, even when it is legally rebuked. It is simply a fact that Chinese officials now occupy several important and influential leadership roles, including in the United Nations, the International Telecommunication Union, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the World Bank.

Unlike many counterparts from liberal democracies, Chinese officials are deeply vulnerable to the whims of Beijing; this was apparent in the downfall of the former head of Interpol, Meng Hongwei, who went missing in 2018 and was purged from the CCP. Meng’s sudden disappearance prompted his wife to speculate that he was being targeted for political reasons.

China has sought to use its influence to reshape discussions about important topics such as telecommunications standards and internet protocols, raising concerns about the abuse of emerging technologies, the use of Chinese companies for surveillance and the misuse of the internet. China’s classification of itself as a “developing” country to receive special benefits has caused frictions in the WTO; the country has also been criticized for using its position in the United Nations to stifle civil society and non-governmental organizations it perceives to be problematic. China has further sought to build international coalitions to push back against claims of Chinese human rights violations and harsh actions in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

China’s flagrant use of economic coercion has also almost certainly intimidated international players, many of whom fear economic harm. Indeed, the fact that so many countries struggle to publicly criticize China is indicative of how successful the country has already been in reshaping the international system over the past several years.

To protect and further its interests, Canada must calibrate its tool kit to address both the weather and climate change.

What Does This Mean for Canada?

To protect and further its interests, Canada must calibrate its tool kit to address both the weather and climate change. While violent Russian aggression rightly demands a strong Canadian response through steadfast commitment to allies and organizations such as NATO, we cannot ignore China’s ongoing long-term efforts to reshape the international order and norms.

A first step will require recognizing that while China’s participation in the international system is not inherently negative, the way the country engages in this system poses long-term challenges to Canada’s interests and values. This necessitates an “eyes wide open” approach that is not built on overreliance on an exchange of Chinese trade for Canada’s prosperity. Canadian policy makers will also need to define and communicate their goals vis-à-vis China, especially to allies who are similarly alarmed about the country’s behaviour.

Importantly, Canada must be present. We should build partnerships with and join groupings of like-minded countries (even those with defence implications) that are focused on the Indo-Pacific. This will require an increased focus on Asia, especially in relation to countries (for example, Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia, South Korea and so on) with which Canada has not engaged substantively in the past.

At the end of the day, and just as with climate change, multilateral efforts will be key to promoting a healthy and stable rules-based international order. Waiting too long will only hurt our chances of turning back the tide.