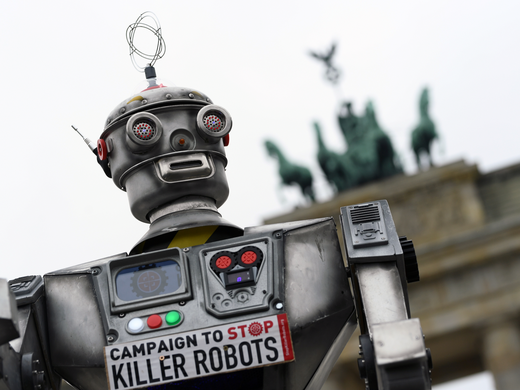

Artificial intelligence’s (AI’s) destructive potential has resulted in a flurry of recent governance activity. Mere days before the United Kingdom hosted its AI Safety Summit from November 1 to 2, the Biden administration announced the Executive Order on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Although the summit in the United Kingdom set out to focus on the catastrophic risks of AI, the US efforts have focused on more concrete issues such as AI’s military uses.

While at the summit, US Vice President Kamala Harris announced several new initiatives that comprised the executive order, such as the new AI Safety Institute. But crucially, Harris also announced that 31 nations had joined the Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy. The declaration was first announced at the summit on Responsible Artificial Intelligence in the Military Domain (REAIM) held in February in the Netherlands.

The update on the declaration signals US commitment to this effort and brings attention to the signatory list that includes US allies such as Australia, Canada and France. Notably missing, though, are China and Russia. The likelihood of either state joining a US-led effort in the current geopolitical climate is exceedingly low.

Russia was not welcome at either summit and is unlikely — with its ongoing invasion of Ukraine — to be brought into these discussions. Even if it were invited, Russia would not likely sign even voluntary documents, as it does not wish to see any regulation, binding or non-binding, on emerging technologies.

China did attend the summits and signed on to two non-legally binding instruments: the REAIM 2023 Call to Action and the Bletchley Declaration agreed to at the UK summit. While important for further dialogue, this obscures a greater obstacle that China poses to AI regulation generally — and specifically to military applications of AI.

While China is unlikely to be as obstructionist as Russia has been in multilateral discussions on autonomous weapons, it is clear it will only agree to non-binding instruments and those that are on its terms. This means that it is unlikely to join the US Political Declaration on Responsible Military Use of Artificial Intelligence and Autonomy due to its strategic interests in relation to the technology and the broader geopolitical competition with the United States.

This was evident when it came to the recent vote on the first-ever resolution on autonomous weapons at the First Committee of the UN General Assembly, which generally notes that states recognize the urgency to address growing autonomy in weapon systems and to hold more talks. While 164 voted to approve the resolution, China abstained.

When crisis scenarios among more adversarial states arise — and they are likely to as more states deploy AI and more autonomous systems in battlespaces — it will be important to have clarity on what is permissible.

China’s abstention highlights that it will try to shape any outcome, including delaying efforts, until the terms are favourable to its ambitions to achieve military AI supremacy.

Only two states voted against the resolution: India and Russia.

Neither vote is surprising given both India and Russia have pushed back against more significant regulatory steps at the UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, or CCW. Indeed, that forum has largely stalled due to the treatment of consensus as unanimity as well as to resistance by India and Russia.

Is the pushback by China, India and Russia insurmountable?

Over the years of discussions on autonomous weapons at the CCW, it has become evident that allies talking to allies does not address the challenge of more adversarial states or states that would be adversaries, primarily for the United States and its allies.

China joining some of these discussions should be welcomed. However, there should be no illusion that the presence of China or its signing of non-binding measures is indicative of its willingness to commit to hard laws on military AI.

Now, this may not appear to be an issue, as neither the United States nor its allies are too interested in hard laws on military AI.

For example, the much-anticipated meeting on the sidelines of the APEC Summit between the United States and China, rumored to result in an agreement banning the use of AI in weapons, drones, and nuclear command and control, ultimately fell short. Instead, the outcome merely acknowledged the necessity for the two countries to work together in addressing these concerns. Notably, it did not even meet the basic threshold of establishing aspirational measures.

However, voluntary agreements and exchanges of information are much easier to achieve with allies. When crisis scenarios among more adversarial states arise — and they are likely to as more states deploy AI and more autonomous systems in battlespaces — it will be important to have clarity on what is permissible, open communication channels, and clear rules guiding uses of AI and autonomy. It is likely sooner rather than later that states will realize the benefit of some legally binding instruments as well.

The political declaration and the first-ever UN resolution on autonomous weapons are important steps forward, as are bilateral meetings between the United States and China. But more governance, including hard laws and complementary processes on military AI and autonomous weapons, is needed. This will require a degree of skilled diplomacy to engage not just allies, but also potential adversaries, and to craft legal agreements. Only then will the risks that come with military AI, such as errors and conflict escalation, be truly addressed.

This piece first appeared in Defense News.