In the late 1990s, after disclosures of gross violations of human rights in Canada’s Indian residential schools over a 150-year period, Canada faced a political, legal and administrative crisis. The shocking revelations presented an opportunity to chart a different course from the destructive relationship between Indigenous peoples and the rest of the Canadian population — a challenge that was met by applying Indigenous solutions. During his term as national chief of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), Phil Fontaine — himself a survivor of residential schools — asserted that the historic opportunity to repair the fractured relationship between Indigenous peoples and Canada would be lost unless Indigenous peoples crafted the solution using their own principles and laws. The prospect of non-Indigenous lawyers, government officials and church representatives controlling the process and deciding the range of reparations and qualifications to obtain them was an anathema to survivors1 who saw it as reinforcing the very colonial dominance that created the residential school policy in the first place. The success of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement is a testament to the effectiveness of Indigenous solutions and their potential use in the resolution of other catastrophes such as those affecting Indigenous lands. If Indigenous legal methods could resolve the dispute — in place of decades-long and costly winner-take-all litigation — it would be possible to achieve honourable solutions benefiting the interests of all sides and protecting the environment for future generations.

The AFN Political and Legal Strategy

During negotiations, the AFN took a number of strategic steps to weave Indigenous legal principles together with other tactics. First, it reached out to survivors, their families and communities to hear what they wanted and needed from a settlement agreement. Second, the AFN jointly convened an international, interdisciplinary conference with the University of Calgary’s Faculty of Law to gain more input. Third, it published the AFN Report, making extensive recommendations for a settlement agreement consistent with Indigenous principles. Fourth, the AFN prepared a business case evaluated by an independent third party showing that the AFN’s proposal was more economically viable than the government’s. Finally, the AFN filed a statement of claim setting out their legal position.

On May 30, 2005, after five months of negotiations between the AFN and Canada and 20 years of litigation with other parties, there was a breakthrough. The AFN entered into a political agreement that committed the federal government to accept the AFN Report as the basis for the settlement agreement, ensuring the AFN’s “key and central” role in achieving a lasting resolution.

Indigenous Legal Theory

As Gordon Christie wrote in his 2009 contribution to Indigenous Peoples and the Law: Cooperative and Critical Perspectives, Indigenous legal theory requires that, as a starting point, reparations must confront the effects of colonialism. Before appropriate reparations can be identified, however, a number of questions must be asked:

- How can we move from Western criteria for reconciliation to an Indigenous understanding of reconciliation?

- How can the relationship be rebalanced?

- How did the residential school policy affect Indigenous identity, relationships, family and citizenship?

- How did the schools affect the economic, cultural and linguistic knowledge of Indigenous peoples?

- How can we make space for Indigenous law, conflict resolution and peacemaking traditions?

Similarly, insights from Indigenous feminist theory guided the AFN to consider the experience of Indigenous women at the intersection of racial, colonial and gendered acts of violence. Here, too, a number of questions must be asked:

- Do the proposals for reparations include Indigenous women’s experiences within the colonial context?

- Was the violence against girls in residential schools perpetuated by colonial social norms in which the degradation of Indigenous women and girls was considered normal or desirable?

- Did residential schools impact Indigenous women and men differently?

- How did the violence in residential schools affect Indigenous women’s experiences in their adult lives, participation in the workforce, or their child bearing and child rearing experiences?

The AFN brought the answers to these questions into the AFN Report, incorporating principles of consultation, consensus, inclusiveness, collaboration, transparency, trust, hope and healing into its work. Guidance from nationwide consultations suggested that survivors wanted a holistic response to the harms committed in and resulting from residential schools, reconciliation and healing, an opportunity to tell their stories, and assurances that no harm would come to survivors and their families. As a result, the AFN ensured that not only were individual survivors of abuse to be compensated but all students who lived at the schools would receive compensation. Recognition of loss of family life, languages, cultures and dignity, the AFN believed, was fundamental to achieving a just settlement. In addition, reparations for intergenerational devastation and commemoration for the dead were covered, as was an early payment for the elderly. Most importantly, a truth and reconciliation commission, research centre, and archive and health supports were established.

Respect for Ceremony

In Ojibway tradition, ceremonies are performed to communicate to the Creator and to acknowledge before others how one’s duties and responsibilities have or are being performed. To honour this tradition in the context of the settlement negotiations, Fontaine (who is Ojibway) invited government officials, church representatives and members of the AFN negotiating team to the traditional roundhouse on the Onigaming First Nation before the negotiations began. A ceremonial pipe was shared, followed by singing, dancing, drumming and praying for a successful outcome to the negotiations. After the ceremony, the group travelled to the national chief’s home community where survivors were invited to ask questions, share their experiences with the negotiators and state their expectations. This reflected Anishinabek law, which focuses on the process and principles that guide actions rather than on specific outcomes. Accountability is closely connected to those to whom duties are owed, how those duties should be exercised and the consequences that flow from such actions.

Applying Indigenous legal principles to the Indian residential school settlement negotiations resulted in outcomes that mainstream courts could not have provided. Direct engagement and consultation, incorporation of ceremonial practices, and a range of holistic reparations that addressed the most important needs of survivors were achieved through the application of Indigenous legal principles.

Indigenous law is evolving out of colonialism, but the journey is far from over. The settlement agreement demonstrates that legal pluralism has the potential to build trust, restore dignity and provide a measure of justice directly to victims, adding to the sum of justice for Indigenous peoples and contributing to reconciliation and transformative change. We have yet to see how these approaches could be integrated into solving environmental challenges on Indigenous lands. The more that Indigenous legal principles are applied to addressing harms and conflicts resulting from colonialism, the more likely it is that lasting reconciliation can be achieved.

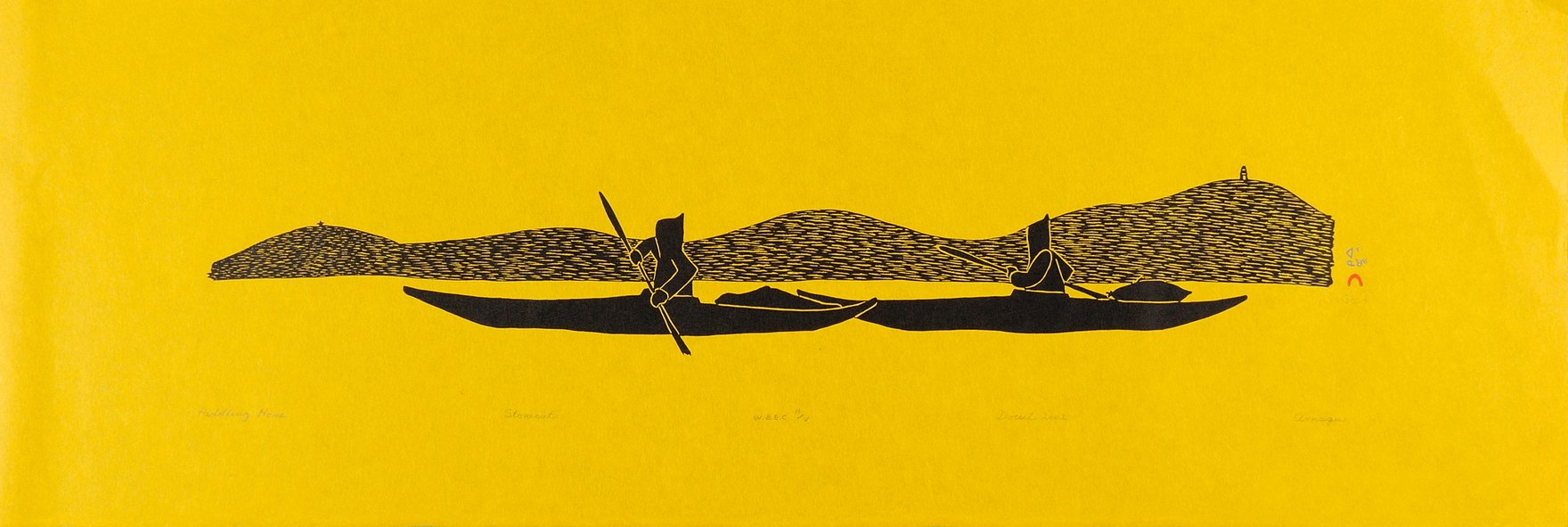

About the artist: Arnaqu Ashevak was an adopted son of celebrated artist Kenojuak Ashevak and a well-known Inuit artist and sculptor. His designs have been featured in several annual collections over the years and he has worked as a printmaker for many local artists.