Given how fast artificial intelligence (AI) tools are improving and how much better they’re becoming at writing text that sounds human, many are beginning to wonder how far off we might be from a textual singularity — a moment when all text online will be presumed to be fake. One source estimates that by 2026, some 90 percent of the Web’s content will be automated. Surely an overstatement, but by how much?

Canada’s Artificial Intelligence and Data Act, now before Parliament, and the European Union’s recently passed AI Act purport to address these concerns by requiring OpenAI, Google and other providers of generative AI to incorporate watermarks — some distinguishing feature showing that a piece of content is AI generated. Efforts to regulate AI in the United States are following suit. One law in China goes so far as to allow companies to provide generated content only if it is tagged as such.

But new laws in Canada and the European Union that propose watermarking as an effective safeguard rely on the premise that it’s technically feasible. This may be so in the case of images, which are rich in data and can easily conceal patterns within an image or be tagged as AI in metadata. But text is not data-rich and therefore is much harder to mark effectively.

As others have noted, creators of AI systems can insert patterns in texts involving punctuation or word patterns that conceal a code. But these can be easily removed with light editing. They can also trigger false positives by coincidental matches. We might try to make the pattern or signature more extensive, but this compromises the quality of the output.

The technical impasse points to two possible futures for text online.

Many AI skeptics wave off concerns about automated text as overstated. Yes, much of the Web will become a “desert” of bots. More of the algorithmic feed of major platforms — Google, Facebook, Amazon — will consist of synthetic text. But we’ll get better at weeding it out precisely because it will always be possible to discern it.

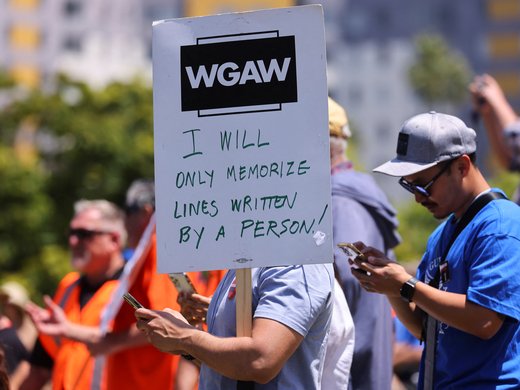

The theory here is that automated text will never become that good. Maybe music or images will, but not text. No matter how advanced GPT-5 or -6 or other models may be, no matter how big or rich the training set, the output will never amount to more than a summary of knowledge or information. It may be more stylish and human-sounding, but never enough to match the authentic, idiosyncratic texture that marks good writing.

More to the point, AI will never be able to generate text that offers the insight or perspective that draws you to sites where you can find an informed take on an unfolding event.

An opposing school of thought isn’t so sure. Maybe some news sources will never be entirely produced by AI. But a future is within sight where chatbots become so capable that much, if not most, of an article in even the most august literary venue is AI generated — and you will not be able to tell. Writing here will contain only sprinkles of human intervention, while in most other places, text will be completely synthetic.

Recent work on the nature of language models and cognition helps us to settle this debate in favour of the skeptics. There are good reasons to believe the textual singularity will never come to pass. Chatbots will not be taking over your favourite literary magazine.

The fear about generative AI becoming so good that it will replace most writing stems from a confusion between “computational” reason and human reason. A new paper by two Oxford researchers draws out the difference in the case of language models in particular, building on a growing body of work that seeks to temper our enthusiasm about the miracle that generative AI represents.

Models create the illusion of intelligence through the magic of predictive algorithms. They work on massive “training sets” of data consisting of earlier text parsed into certain patterns. When a bot generates text in response to a prompt, it’s really performing a kind of translation of the earlier text it was trained on. What looks to us like intelligence is, the Oxford researchers explain, largely an “epiphenomenon of the fact that the same thing can be stated, said, and represented in indefinite ways.”

The currently fashionable solution to the problem of language model hallucination or gaps in knowledge — in which AI generates text that is incorrect or nonsensical is — retrieval-augmented generation. Before Bing Chat, which harnesses GPT-4, responds to your prompt, it confirms any factual claims by consulting the Web. But this only extends the currency of its training data to a few minutes ago. It doesn’t address the deeper problem that a chatbot can only repeat what has already been said.

Stepping back, we can see that language models may become better at imitating human language, and may sound more convincing to us as human. But the qualitative difference they will never overcome is a fundamental staleness in thought. They can only ever summarize, translate, reformulate. They can’t offer a novel theory, a genuine insight, a paradigm shift.

The best policy response to fears of the net being taken over by bots is to cultivate a reputation for insight, authenticity and truth. In this version of the future, AI doesn’t pose a threat so much as it helps to make our goals and values clearer.

This article first appeared in Newsweek.