Canada is rich with natural resources — oil and gas, minerals, forests, fish and water. As the exploitation of these natural resources often takes place on the traditional territory of Indigenous peoples, they are disproportionately impacted by the adverse effects — and potential risks — associated with this resource development. Federal and provincial environmental assessment (EA) processes are used to assess the potential risks and adverse effects associated with project-level resource development. By virtue of section 35 of the Constitution Act, Indigenous peoples are also consulted and accommodated when their rights or title might adversely be affected by project development. However, once these processes are complete, decisions about whether a project may proceed rests with the federal or provincial government. This is so even when Indigenous peoples and their traditional territories are exposed to significant risks and adverse effects. As a result, the EA process is viewed by some Indigenous peoples as “a final tool for the disposition/disconnection of their rights and culture.” Outside these settler processes, however, Indigenous peoples have proactively begun to exercise inherent rights to develop independent assessment processes based on revitalized Indigenous laws. In so doing, Indigenous peoples are beginning to make space for shared decision making relating to the management and use of resources within their traditional territories.

In Canada, most resource development proposals that have the potential to significantly impact the environment trigger federal and/or provincial EA processes. Federal EAs are currently carried out in accordance with the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012 (CEAA 2012). The federal EA legislation is used to predict the environmental effects associated with a proposed resource development project and to consider the available mitigation measures to reduce or avoid those environmental effects. This allows decision makers to make informed decisions as to whether proposed projects should proceed. Changes in the environment that may affect health and socio-economic conditions; physical and cultural heritage; the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes; or any structure, site or thing that is of historical, archaeological, paleontological or architectural significance must be taken into account. If the EA process predicts the proposed project has the potential to cause significant environmental impacts, the Governor-in-Council determines whether those impacts are justified in the circumstances.

Aimed at the approval of “less bad projects,” under CEAA 2012 the vast majority (95 percent) of projects that have moved through the federal EA process have been approved. And, even when the CEAA 2012 EA process has predicted significant environmental effects, 73 percent (11 in total) of the proposed projects have been approved following a “justified in the circumstances” determination by the Governor-in-Council. Many of these projects relate to resource development located within the traditional territories of Indigenous nations, with potentially significant adverse effects on water quality, birds, fish, caribou, use of land and resources for traditional purposes, and Aboriginal rights and culture associated with various projects determined to be justified in the circumstances. The Governor-in-Council is not obligated to explain why these types of significant impacts are “justified in the circumstances.” It is implicit, however, that in such cases there is a trade-off between the potential benefits associated with the project and interference with the rights of Indigenous nations to own, use, develop and control their lands, territories and resources as contemplated in article 26(2) of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). And, while the duty to consult and accommodate operates alongside the EA process, as currently articulated, this duty falls short of the “apparently more demanding duty” to seek free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) under article 32(2) of UNDRIP.

Canada now supports UNDRIP “without qualification” and has committed to its implementation. Still, the federal government’s proposed impact assessment legislation, Bill C-69 — which does indicate an expanded role for cooperation and substitution of assessment processes with recognized “Indigenous governing bodies,” and its preamble gives a nod to the Government of Canada’s commitment to implementing the declaration — keeps decision-making power within the federal government. An attempt in the Senate Standing Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources to amend Bill C-69 to require consideration of whether government approval of a project “would be consistent with the Government of Canada’s commitment to implementing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” did not pass.

Indigenous nations have responded to the inadequacies in these settler processes in different ways. Often they challenge resource development approvals in court on the basis of failures in the EA process and/or failures in the government’s discharge of its duty to consult and accommodate. Indigenous nations are also challenging “the ‘consultation’ assessment model” imposed by settler EA processes with new models “based on our full informed consent” by asserting inherent rights to control their lands, territories and resources and implementing independent assessment processes based on their own revitalized Indigenous laws. It is these assessment processes led by Indigenous nations that may make space for Canadian assessment processes to align with the principles of UNDRIP. To illustrate this point, two examples of independent assessment processes led by the Stk’emlupsemc of the Secwepemc Nation (SSN) and the Squamish Nation are considered here. A third example, an independent assessment undertaken by the Tsleil-Waututh Nation in relation to the proposed Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, will be considered by Darcy Lindberg in this essay series.

The first Indigenous nation to take this step was the SSN. Faced with a proposed copper/gold mine project at Pípsell, a “cultural key-stone place” within their traditional territory, the SSN asserted title over their traditional territory and initiated an SSN assessment process of the mine based on SSN laws. At the completion of the assessment process, the SSN determined it would not give its FPIC to the development of the lands and resources at Pípsell for the purposes of the proposed mine. In addition, the information provided through the SSN assessment process was embedded and considered in the joint federal comprehensive study and provincial assessment report and informed the federal minister of environment and climate change determination that the proposed project was “likely to cause significant adverse environmental effects and cumulative effects to Indigenous heritage and the current use of lands and resources for traditional purposes by Indigenous peoples.” The Governor-in-Council ultimately decided that the significant adverse environmental effects associated with the proposed mine project could not be justified in the circumstances.

The Squamish Nation has also asserted an inherent right to govern its land and, in accordance with that right, created an independent assessment process for proposed development projects within its territory. The assessment process is designed to allow the Squamish Nation to make informed decisions as to whether to consent to proposed projects, with a view to sharing in the final decision making following government EAs. The Squamish Nation process operates by way of EA agreements with project proponents. A contractual arrangement between the parties, the agreement establishes the terms and conditions of participation in a confidential process that runs alongside the government EA processes. If approval is warranted, the Indigenous nation issues a legally binding environmental certificate establishing the conditions of approval. The process is voluntary for project proponents, who agree to pay process fees that fully fund the assessment, but the opportunity to receive the nation’s consent provides the incentive to participate. In turn, the Squamish Nation has a mechanism to provide its FPIC on agreed conditions. In its first independent assessment, the Squamish Nation consented to, and issued an environmental certificate subject to several legally binding conditions, to a Woodfibre LNG project. Following a federal EA, the federal government also approved the project, agreeing at the request of the project proponent to amend a federal condition in order to allow the proponent to comply with a condition in the Squamish Nation environmental certificate.

Each of these assessment processes offer powerful examples of Indigenous nations stepping out from under the “consultation” assessment model imposed by settler EA processes toward models built on achieving informed consent. As Canada moves to implement UNDRIP, the challenge is for government assessment processes to create a space within which to allow for shared decision making.

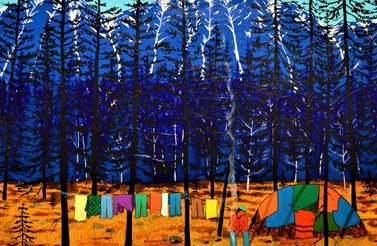

About the artist: Shuvinai Ashoona is an Inuk artist born in Cape Dorset, who works primarily in drawing. She is known for her detailed pen and pencil drawings depicting northern landscapes and contemporary Inuit life. Ashoona's drawings are sometimes rooted in nature, but other times drawn from imagination, creating a claustrophobic, dense effect. Shuvinai Ashoona was awarded the 2018 Gershon Iskowitz Prize for her outstanding contribution to the visual arts in Canada.