he COVID-19 pandemic has been a siren call for stronger action in the face of global threats. What has been described as the collision of this pandemic with a series of recent extreme weather events has amplified this call, providing a frightening glimpse into the scope of the grim challenges lying in store as the effects of climate change become more prevalent and pronounced.

Infectious Diseases, Pandemics and Climate Hazards

The alarm bells have been ringing for a while. We have all heard the acronyms: SARS [severe acute respiratory syndrome] in 2002; H1N1 [swine flu] in 2009; MERS [Middle East respiratory syndrome] in 2012; and now, along with COVID-19, there are reports of a “new emerging flu strain” being found in Chinese pigs.

Perhaps not surprisingly, there is growing evidence that many of the same human activities that are contributing to climate change are also contributing not only to the emergence of new diseases but also to their spread. Research is providing compelling evidence of the extent to which climate change is actually influencing the evolution of organisms in ways that give rise to human diseases. According to Daniel R Brooks, professor emeritus of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto, “We live in a world in which human population expansion and increased density, and increased globalization of travel and trade act synergistically with climate change to produce an explosive emerging disease crisis that represents an existential threat to technological humanity.”

So, rather than being discrete threats that just happen to collide, pandemics and climate change are, in effect, co-travellers.

Furthermore, these same climate conditions that are contributing to the increase and diversity of emerging diseases also shape their human encounters.

Extreme weather events and accompanying natural disasters, such as floods, droughts, heat waves and wildfires, are becoming commonplace as the effects of climate change tighten their grip on the planet. The advent of terms such as “mega fires” and “super storms” together with seemingly endless news coverage of “record-breaking” weather events are the public face of a predicted consequence of climate change: climate change increases the frequency and intensity of severe weather events.

In late May 2020, as COVID-19 was spreading rapidly around the globe, one of the most powerful storms in decades plowed into the east coast of India. In anticipation, some 3 million people were evacuated into crowded cyclone shelters. Many refused to evacuate out of fear of contracting the virus, an unknown number of whom were killed as the cyclone ripped through their ramshackle coastal villages. The extent to which the virus was able to spread due to the evacuations has yet to be assessed.

Almost simultaneously, half a world away, two dams on the Tittabawassee River in the US state of Michigan were failing after record flooding from intense rains. As the waters rose, Governor Gretchen Whitmer declared a state of emergency and pleaded with residents in the floodplain to evacuate immediately. Michigan, at the time, was being particularly hard hit by COVID-19 and the state had, despite considerable opposition, implemented far-reaching lockdown and quarantine measures. Imploring the evacuees to continue observing virus precautions as much as possible, Whitmer remarked, “It’s hard to believe that we’re in the middle of a 100-year crisis, a global pandemic, and we’re also dealing with a flooding event that looks to be the worst in 500 years.”

The broader truth, of course, is that this scenario was entirely too believable.

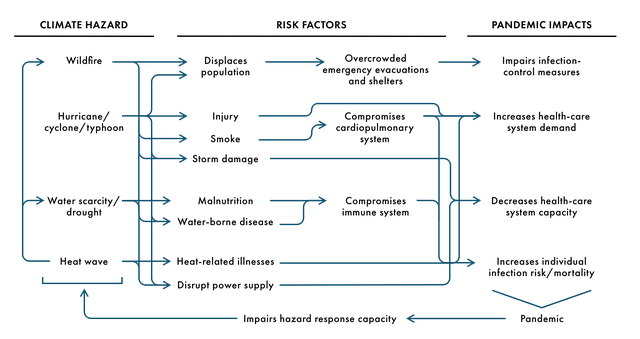

The basic logic of the risks in an overlap between the pandemic and extreme weather events is straightforward (see flow chart). Take, for example, the southern US hurricane zone. During the record-setting 2017 season, three Category 4 hurricanes made landfall in the United States, displacing tens of millions of people and causing extensive damage to critical infrastructure, including severe damage to health-care capacity.

During a pandemic, the hurried displacement of millions of people during a storm increases the risk of exposure to the virus as maintaining adequate precautionary regimes becomes difficult, if not impossible, as does effective contact tracing of new cases among evacuees. Once the storm has passed, residents face the always daunting task of cleanup and repair, made more difficult because of necessary virus protection measures. Storm-battered health-care facilities, assuming they remain operational, face the challenge of accommodating an influx of storm-related cases.

This year, as the scope of the pandemic became clear, in anticipation of what one news bulletin would later describe as an “unrelenting crush of cases and deaths,” many health-care jurisdictions moved quickly to reconfigure their facilities. Non-emergency services were scaled back and elective procedures were postponed, as were diagnostic testing and many forms of treatment — all in preparation to meet the demands of isolating and treating a rush of pandemic-related victims.

Coming on top of the pandemic caseload, hurricane victims must be kept separated to reduce the risk of transmission. In the event of widespread storm damage, such as what was sustained during the 2017 hurricanes, state health-care systems could quickly be overwhelmed, seriously increasing the toll of both the pandemic and the storm.

So, basically, climate change helps foster the conditions for the emergence of new pandemics and for increasing their lethality. Climate change is a pandemic enabler, a pandemic accelerant and a multi-pathway crisis engine. COVID-19 is screaming to us that our health and our planet’s health are inextricably intertwined. The same conditions that contribute to climate change, contribute to pandemics. Investing in the mitigation of these conditions yields a double reward. Failure to invest yields an exponential increase in risk.

The Long and Winding Road

We’ve all heard the liturgy of ideal-type strategies for mitigating the challenges of climate and pandemic risks. Such calls emphasize the necessity of capable domestic authorities working together in close international cooperation, taking bold, coordinated and far-reaching remedial action while generally building resilience and strengthening inclusive and equitable governance.

While the need for such strategies is undoubtedly true, this is most certainly not the setting we find ourselves in currently.

Sadly, the resources at hand for achieving such epic levels of cooperation are seriously lacking. Autocrats and totalitarians are taking advantage of global confusion to consolidate their power and extend their influence. Political polarization and hyper-partisanship, surreptitiously encouraged by malign actors both domestic and foreign, are a pandemic of another sort corroding the democratic integrity of too many leading democracies.

In April 2020, as the virus outbreak had begun its rapid spread, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists highlighted how “COVID-19 brings into sharp relief how catastrophe feeds on dysfunction in national and international governance. The pandemic has illustrated, all too well, the diminishment of crisis management infrastructure, [and] the decreased commitment to international cooperation.” The Bulletin Science and Security Board went on to decry the “disturbing trend, in which influential leaders had denigrated and discarded the most effective methods for addressing complex threats — international agreements with strong verification regimes — in favor of their own narrow interests and domestic political gain.”

Almost as if to prove this contention, the US administration announced, in late May, its intention to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO), accusing the body of colluding with China to cover up the extent of the threat posed by the virus and generally mismanaging the crisis.

In late June, 100 days after the WHO officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic, an exasperated UN Secretary-General, António Guterres, in an interview, pleaded for greater international cooperation, warning that “there is total lack of coordination among countries in the response to the COVID,” and how “they are creating the situation that is getting out of control.”

Autocrats and totalitarians are taking advantage of global confusion to consolidate their power and extend their influence.

Growing antipathy, even outright hostility, toward international institutions threatens scarce avenues for sustained international cooperation, and the pandemic has brought the frayed state of global governance into sharp relief. Early efforts at cooperation and collaboration among nations at the outbreak of the epidemic gave way to increasing interjurisdictional competition, growing polarization and creeping anti-science, self-help and beggar-thy-neighbour rhetoric in various public fora. There is now a growing recognition that we can “expect many countries will have difficulty recovering from the crisis, with state weakness and failed states becoming an even more prevalent feature of the world,” threatening a prolonged period of dangerous global instability.

Together with all of this, weak global performance toward Paris Agreement climate targets, especially by major industrialized countries, has, likewise, highlighted the limits of relying upon international cooperation to achieve meaningful progress arresting climate change. Climate change, the enabler and accelerant of this mess, continues unabated.

By far the biggest elephant in the geopolitical room lies just south of the Canadian border.

It is an understatement to say that the United States — the world’s postwar hegemon and its largest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions — is in a period of profound political turmoil. A disastrous and rapidly deteriorating pandemic response has only worsened this situation, and the prospects for a marked deterioration in the political climate in advance of the upcoming November election are high. Adding in the high risk of a devastating hurricane season comparable to that of 2017 will ravage already pandemic-scarred southern US states and could well push this deterioration toward a general breakdown in democratic governance.

The consequences of such an outcome are truly grim to contemplate, posing a political and economic as well as an intelligence and security nightmare for all Western democracies, Canada in particular. But the too-real prospect of seeing this scenario or something approaching it unfold underscores the urgency of recognizing the threat posed by what may quickly become an extraordinary cascade of shocks.

One Common Thread

Weaving through all these varied elements, we can trace the thread of “social media’s illiberal intent” — with its “design optimized for engagement over truth and prioritizing virality over the quality of information,” it has fostered confusion, dissension and profound obstacles for governance. We can see the result of this “false information plague” in the dangerously corrosive effects that misinformation and disinformation and the weaponization of social media can have on the health of a democracy and its ability to function effectively exemplified by the current US political context. We can see it in the anti-science and anti-expert ethos that has infected so much of the climate change and pandemic response “debates” — a small but telling example of which are recent reports of US public health officials leaving their jobs after facing public abuse and threats of violence following their announcement of pandemic control measures unpopular in some constituencies.

Across Western democracies, we can see how the weaponization of social media has also contributed to the increase in anti-immigrant and far-right nationalism and to the increasing disdain for international cooperation and international organizations more generally. Around the world, pandemic-driven social media disinformation has impeded effective public health governance while also fostering elaborate scams and profiteering rackets.

As prominent journalist Maria Ressa has observed: “This is democracy’s death by a thousand cuts.”

Canada’s Path Forward

So, what about the Canadian context?

With some notable and tragic areas of exception, Canada has, so far, fared reasonably well through the pandemic — exceptionally well compared to its superpower neighbour immediately south — but challenges lie ahead. Barring the discovery of a vaccine or reliable treatment protocol, the pandemic is far from over and, as it drags on, risks will increase. Then begins the next great struggle as the country transitions out of its pandemic response and toward some new and unknown normal.

Canada is vulnerable. The country, working with diminished capacity, will face innumerable difficult choices with respect to the adoption of priorities and policies to guide the scope and direction of its efforts to recover from the deep economic and social damage left behind by the pandemic while balancing the federation’s traditional competing interests. This recovery will need to happen within a radically changed and dangerous geopolitical space while simultaneously confronting a looming climate crisis.

As Canada’s federal and provincial governments move to implement necessary, but quite likely unpopular, policies, maintaining public trust in and support for the country’s democratic institutions will be essential. Governments will have to be hypervigilant in guarding against any threats to the social fabric that might undermine this trust. Under these conditions, the risk is high that all aspects of the recovery effort, but the broader strategic imperative of bold action to mitigate climate change in particular, will face a potentially crippling phalanx of overt political opposition coupled with more covert efforts to undermine government legitimacy.

And then, there’s the elephant.

The potential risks to Canada of a protracted period of political turmoil in the United States cannot be ignored. Given the extent of the integration of the two countries’ economies, Canada’s successful post-pandemic recovery is heavily dependent upon a swift and successful US recovery. Anything short of that will pose immense challenges to Canada’s prosperity and security and, by extension, to its capacity for democratic governance.

It is in this troubled context that we urgently need to start a conversation about the proper role of the intelligence and security community in protecting these institutions of democratic governance — most especially from threats originating in the online space — thus preventing democracy’s death by a thousand cuts.

The traditional notion of the “telling truth to power” role of intelligence services will need to evolve. Moving beyond conventional notions of cybersecurity and cyber defence, what expanded role is appropriate for the community in the online space? How can the community contribute to the institutionalization of capacity to distinguish truth from alternative facts and information from disinformation — how do we harden the country’s truth infrastructure? How do we build capacity to protect Canada not only from malign foreign governments but also from the increasingly serious threats posed by internet trolls, bots, conspiracy theory peddlers and hyper-partisan malcontents?

The question of content moderation and how to balance the value of free speech with the need to protect citizens from harms caused by speech is crucial in this regard, but is unlikely to find sufficient airtime in the near term to generate anything but the most rudimentary of answers. Likewise, calls for improved global governance of social media and related digital platforms are unlikely to produce meaningful near-term results in the post-pandemic transition period.

To date, the role of Canada’s security and intelligence community in the digital space has focused on combatting foreign-state-based cyber interference, cyber fraud and related criminal activity, and the provision of public warnings and advice related to cyber threats. The task of preventing the anti-democratic manipulation of the social media and digital space is left up to the social media platforms themselves. The question here is whether counting on social media’s self-regulation alone is sufficient in the face of the potentially profound near-term risks facing the country.

The challenge for every democratic state will be to weather the storm while sustaining, if not strengthening, their core democratic principles.

If not, how might the community usefully help to harden and safeguard Canada’s democracy against these threats until such time as a robust global governance regime can be realized? Would such work be an appropriate expectation for the intelligence and security services within the Canadian democracy?

All of these questions lead to the considerably thornier consideration of whether there is a role for these services in protecting us from ourselves. Contemplating unorthodox and possibly anti-democratic measures to secure democratic institutions through the near term may be unavoidable (the obvious example being the extension of the mandate to combat foreign interference campaigns against democratic institutions to include domestic interference, misinformation and disinformation campaigns). Although potentially contentious, in Canada, the traditional ethos of peace, order and good government privileges the collective over the individual, suggesting that measures that might impinge upon the privacy or the freedom of the individual would be conscionable in the service of securing the collective in a time of crisis.

More prosaically, though, the probable scope of any intrusion is unlikely to exceed that which most social media users freely concede to their various platform suppliers under the terms of licensing, service or user agreements.

Peace, order and good government can also serve as a useful metric for setting boundaries for prospective intelligence and security service activities (activities demonstrably in service of these objectives would be acceptable, while those straying toward other ends, such as economic prosperity or some particular conception of “national interest,” would not be acceptable).

There is no state self-help solution to climate change. Efforts to bring this pandemic to a close and repair the damage it has wrought, efforts to forestall future pandemics and efforts to make meaningful progress in halting the progress of climate change — all will ultimately demand sustained international cooperation if they are to be comprehensive and effective. Hopefully, with the end of the pandemic will come a period of transition toward an era of significantly renovated international collaboration. The near-term signs, however, are that this will be a difficult, costly and quite possibly violent transition as great powers realign and rising and middle powers forge new alliances to help each other survive and pursue common goals.

The challenge for every democratic state will be to weather the storm while sustaining, if not strengthening, their core democratic principles. This is likely to be a very messy process as democracies globally relearn the benefits of trust and cooperation, working together to advance these principles within their collective and, more broadly, within states with less governance capacity.