n iconic cartoon dating back to 1993, early in the internet era, suggested that the internet provided openness with speed and — above all — anonymity. On the internet, nobody knew you were a dog. Twenty-five years after the cartoon was published, we know otherwise. On the internet, everyone knows you are a dog — as well as knowing what kind of biscuits you like, how often you go for a walk and where, who you bark at and where your favourite fire hydrant is.

This loss of privacy is accompanied by the technological change that big data fuels, and because of the radical change in employment patterns and lifestyles that artificial intelligence and robotics hold, concerns about data verge on being existential. But consequences are not entirely inevitable — they can be generated by deliberate action and policy choices, provided we have the right national discussion about the options.

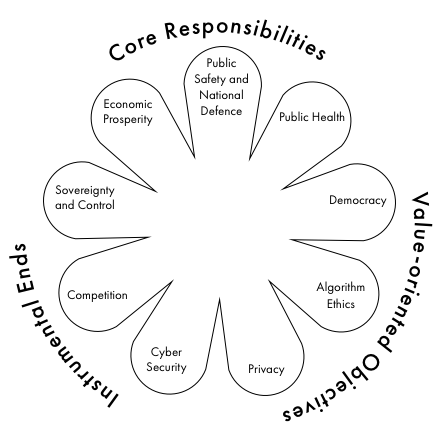

Figure 1: A National Data Framework

The central message of the essays in this series is that governance in the age of big data is about achieving multiple, sometimes conflicting, ends. These, in turn, raise public policy questions that must be addressed if a coherent strategy around data is to be shaped. The whole may be presented as a mandala, a concept whose application in this context we owe to Jim Balsillie.

The reflection, harmony and balance that mandalas portray is for an ideal universe. In reality, trade-offs (for example, between security of financial data and efficacity of payment systems) have to be faced and choices made. The central questions around data governance boil down to these:

- Who owns the data and what do these data rights entail?

- Who is allowed to collect what data?

- What are the rules for data aggregation?

- What are the rules for data rights transfer?

In the social sphere, we should address these questions:

- What are the “mental health” issues, especially for youth, from surveillance capitalism?

- How do we protect all citizens, but especially vulnerable groups, from this?

- How do we ensure that surveillance for legitimate purposes, such as fighting crime and maintaining public security, is not abused to reduce democratic rights and freedoms?

- How do we enhance regulation and monitoring of political messages and advertising?

The cyber arena yields additional questions:

- How do we make public and private assets safer from cyber threats?

- How do we ensure sovereign capabilities for our military?

- How do we establish and enforce new global cyber norms?

To maximize the commercial potential of data, we should ask:

- How can data strategies better support innovation outcomes?

- What are the individual firm and collective capacities needed to capitalize on this?

- How to pick data industries to back?

Finally, there are questions around the global governance dimensions of data:

- What should the international rules governing the trade of data be?

- How are diverse sovereign choices supported?

- How is flexibility preserved to allow ongoing innovation and proper utilization?

- Is it too soon to encode data provisions in international agreements?

At CIGI, we hope the issues and ideas discussed in the essays in this series will contribute to informed decisions on data governance — both nationally and internationally — going forward.