latforms are hardly a new phenomenon1 and include newspapers, stock markets and credit card companies. And although more recent than traditional platforms, online platforms have been around since the early days of the World Wide Web, with early examples such as America Online (or AOL, as it later became known), Netscape and Myspace typifying these “as digital services that facilitate interactions between two or more distinct but interdependent sets of users (whether firms or individuals) who interact through the service via the Internet” (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] 2019a, 11). Such platforms are said to be two-sided or, in some cases, multi-sided, with each side having its own distinct set of services that appeal to different audiences.

What differentiates today’s online platforms are a number of economic properties fuelled by the digital transformation that have led to a new cadre of platforms with a global reach, trillion-dollar valuations and huge profits that feed large research and development (R&D) efforts, as well as significant merger and acquisition activity, and ever-growing engagement in public affairs. These characteristics include powerful network effects; cross-subsidization; scale without mass, which enables a global reach; panoramic scope; generation and use of user data to optimize their services; substantial switching costs; and, in some markets, winner-take-all or winner-take-most tendencies. Skillfully exploiting these properties, online platforms have become very popular, and we now depend on them for everything from entertainment and news to searching for jobs and employees, booking transportation and accommodation, and finding partners.

Their popularity underscores the fact that online platforms have brought benefits to economies and societies, including considerable consumer welfare. They also raise a new set of important policy challenges, ranging from the classification of workers (for example, contractors versus employees) to the misuse of user data to the adverse impacts of tourists in city centres. Likewise, some online platforms have drawn the attention of competition authorities and other regulatory bodies to issues ranging from abuse of dominance to taxation.

That inadequacy has prompted leaders of some technology companies to ask for a new regulatory scheme.

The growing prominence of these issues on policy agendas at both the national and the international level provokes a more fundamental question about how to craft an appropriate model of governance that strikes the balance between, on the one hand, promoting online platform innovation and productivity and, on the other hand, achieving basic policy objectives, such as ensuring sufficient competition, protecting consumers and workers, and collecting tax revenue. It is clear that many of the regulations designed for traditional businesses are not a good fit for online platforms. In the last few years, that inadequacy has prompted leaders of some technology companies to ask for a new regulatory scheme. Testifying before the US Congress, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg stated: “My position is not that there should be no regulation....I think the real question, as the Internet becomes more important in people’s lives, is what is the right regulation, not whether there should be or not” (CBC 2018). Microsoft President Bradford Smith has stated a similar position regarding facial recognition software, saying that “we live in a nation of laws, and the government needs to play an important role in regulating facial recognition technology” (Singer 2018).

But regulating these businesses is far more complex than the political debate would suggest, largely because platforms vary significantly, rendering any omnibus “platform regulation” unsuitable. The OECD recently undertook in-depth profiles of 12 successful online platform firms and found that they differed widely on a number of different axes (such as size, functionality, income and profitability) and cannot be compartmentalized into just a few categories, let alone a single sector (OECD 2019a, 12). They differ in how they generate income, with some drawing revenue from advertisers, others from transaction fees, still others from subscriptions and some from a combination of those. Online platforms serve different needs of different customers looking for different things. Indeed, it is striking how many different economic activities online platforms encompass.

Another factor that tends to be overlooked in the current debate about online platforms is the rise of Chinese platforms, which yet again add to the diversity. Policy makers’ attention, understandably, has been largely focused on the big Western platform companies, in particular, Amazon, Apple, Facebook and Google. Discussions are under way about placing new regulations on them and even about breaking them up. Conversely, sparse attention is being devoted to preparing for the expansion of the major Chinese platform firms: Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent (ibid.). While their platforms have been seen as being largely confined to China, this is quickly changing, due in large part to the integration of mobile payment apps into the platforms. For example, Tencent’s WeChat Pay is already available in 49 countries outside of China (Wu 2018). This access will only grow as merchants move to serve Chinese tourists, already the number-one tourist demographic both by number and money being spent (OECD 2019a, 77-78). Given the global reach of the online platforms, it is important that a debate about governance schemes be forward-looking and take into account all the big global players.

As eager as policy makers are to act, effective policies need careful deliberation. Ex ante regulation can be problematic if it’s not fully grounded in experience and insight, characteristics that can be difficult to achieve in periods of rapid transformation awash in steady streams of new technologies. Ex post regulation may face resistance from embedded interests, including dedicated user bases. At the same time, when policy intervention is either too frequent or absent altogether, uncertainty arises, which may limit investments and innovation. Countries with a well-established and elaborated policy framework and constituencies built up over hundreds of years may be disadvantaged relative to emerging economies or countries that have recently switched from one system (for example, communism) to another, providing them with “leapfrog” opportunities. To add to this list of considerations, online platforms with two- or multi-sided markets frequently have product scope (providing information services as well as, say, financial payments and the provision of media) that crosses traditional policy domains segmented by government ministries and agencies, requiring a joined-up approach to policy.

The traditional “end-of-pipe” regulation that focuses on a single final product and tries to fit that to an existing policy framework is ill-suited to highly innovative and dynamic online platform businesses with global reach. Instead, a new, more anticipatory and upstream approach is needed,2 one that uses the multi-stakeholder model to collectively shape developments so that innovation is encouraged and productivity-boosting disruption enabled, but within a set of publicly defined policy objectives.

Moving Upstream

The governance of emerging technologies poses a well-known puzzle: the so-called Collingridge dilemma holds that early in the innovation process — when interventions and course corrections might still prove easy and cheap — the full consequences of the technology — and hence the need for change — might not be fully apparent (Collingridge 1980).

Conversely, when the need for intervention becomes apparent, changing course may become expensive, difficult and time- consuming. Uncertainty and lock-ins are at the heart of many governance debates (Arthur 1989; David 2001) and continue to pose questions about “opening up” and “closing down” development trajectories (Stirling 2008).

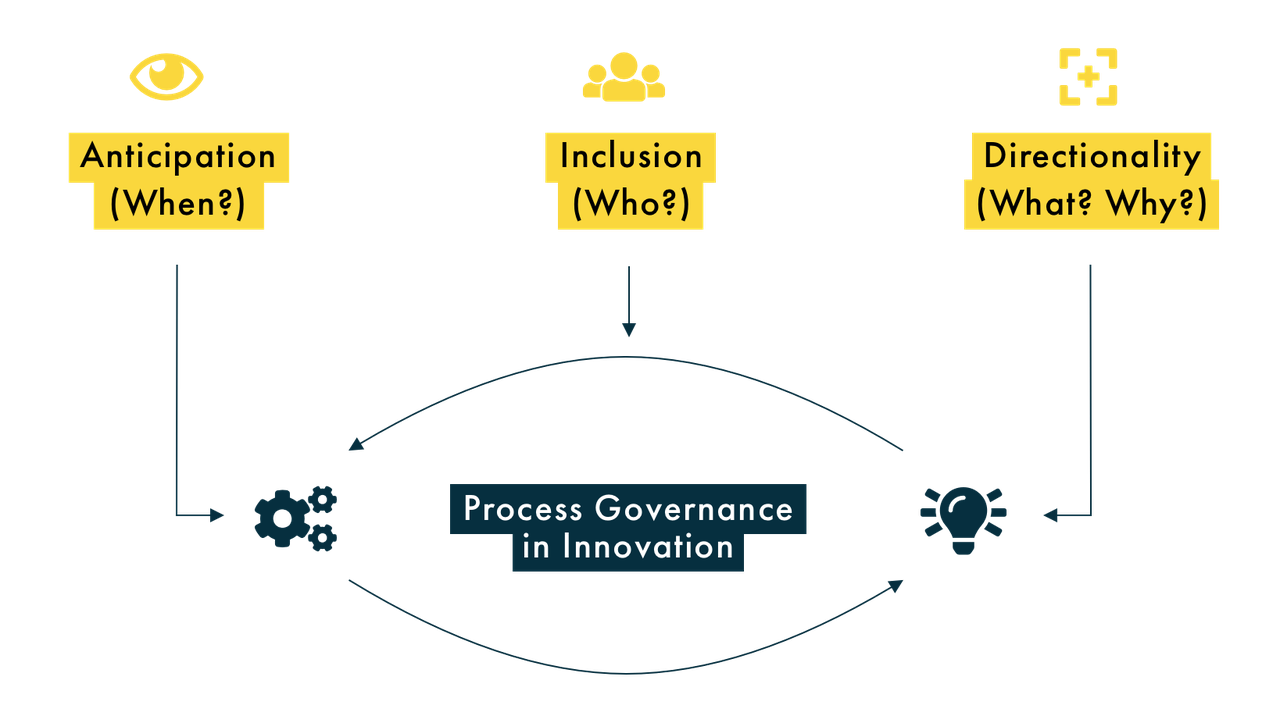

Several emerging approaches in science policy seek to overcome the Collingridge dilemma by engaging concerns with technology governance “upstream.” Process governance shifts the locus from managing the risks of technological products to managing the innovation process itself: who, when, what and how. It aims to anticipate concerns early on, address them through open and inclusive processes, and steer the innovation trajectory in a desirable direction. The key idea is to make the innovation process more anticipatory, inclusive and purposive (Figure 1), which will inject public good considerations into innovation dynamics and ensure that social goals, values and concerns are integrated as they unfold.

Figure 1: Three Imperatives of a Process-based Approach to Governance

Artificial Intelligence as a Test Case

While governments have experimented with policies that seek to move upstream by adopting a process-based approach to governance, the global nature of online platforms, which are currently some of the largest actors in artificial intelligence (AI), demands an international approach — a requirement all the more challenging to meet when the relevancy of many multilateral institutions is being questioned.3

AI, which owes some of its recent advances to innovations from online platforms (whose R&D spending on AI dwarfs that of any countries’ investment in it), presents itself as a classic case warranting a process-based approach to governance. AI is reshaping economies, promising to generate productivity gains, improve efficiency and lower costs. It contributes to better lives and helps people make better predictions and more informed decisions. At the same time, AI is also fuelling anxieties and ethical concerns. There are questions about the trustworthiness of AI systems, including the dangers of codifying and reinforcing existing biases, or of infringing on human rights and values such as privacy. Concerns are growing about AI systems exacerbating inequality, climate change, market concentration and the digital divide.

AI technologies, however, are still in their infancy. At a Digital Ministers Group of Seven (G7) meeting in Takamatsu, Japan, in 2016, the Japanese G7 presidency proposed the “Formulation of AI R&D Guidelines” and drafted eight principles for AI R&D. Japan began to support OECD work on AI, multi-stakeholder consultations and events, and analytical work (OECD 2019b). G7 work on AI was furthered in 2017, 2018 and 2019 under the Italian, Canadian and French presidencies, with ministers’ recognition that the transformational power of AI must be put at the service of people and the planet. In this sense, the G7 had begun to espouse the “anticipation” imperative of process governance.

In May 2018, the OECD’s Committee on Digital Economy Policy (CDEP) established an Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AIGO) to explore the development of AI principles. This decision effectively echoed the G7 call for anticipation and took a multi-stakeholder inclusive approach. The AIGO consisted of more than 50 experts, with representatives from each of the stakeholder groups, as well as the European Commission and the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. It held meetings in Europe, North America and the Middle East, and produced a proposal containing AI principles for the responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI. This work was the basis for the OECD Council’s eventual recommendation on AI, which the CDEP agreed to at a special meeting in March 2019, and recommended the OECD Council, meeting at ministerial level, adopt. That adoption occurred in May 2019 when 40 countries adhered to the recommendation.4

In June 2019, the Group of Twenty (G20) Ministerial Meeting on Trade and Digital Economy in Tsukuba adopted human-centred AI principles that were informed by the OECD AI principles.5 This action vastly improved the global reach of the principles.

Another option to spur faster and more effective decisions is the use of digital tools to design policy, including innovation policy, and to monitor policy targets.

The OECD AI principles focus on features that are specific to AI and set a standard that is implementable and sufficiently flexible to stand the test of time in a rapidly evolving field. In addition, they are high-level and context-dependent, leaving room for different implementation mechanisms, as appropriate to the context and consistent with the state of art. As such, these principles effectively provide directionality for the development of AI. In this way, they provide an example of a possible new governance model applicable to platforms as they signal a shared vision of how AI should be nurtured to improve the welfare and well-being of people, sustainability, innovation and productivity, and to help respond to key global challenges. Acknowledging that the nature of future AI applications and their implications are hard to foresee, these principles aim to improve the trustworthiness of AI systems — a key prerequisite for the diffusion and adoption of AI — through a well-informed whole-of-society public debate, to capture the beneficial potential of AI, while limiting the risks associated with it.

Importantly, the principles also recommend a range of other actions by policy makers that seek to move governance upstream, including governments using experimentation to provide controlled environments for the testing of AI systems. Such environments could include regulatory sandboxes, innovation centres and policy labs. Policy experiments can operate in “start-up mode.” In this case, experiments are deployed, evaluated and modified, and then scaled up or down, or abandoned quickly. Another option to spur faster and more effective decisions is the use of digital tools to design policy, including innovation policy, and to monitor policy targets. For instance, some governments use “agent-based modelling” to anticipate the impact of policy variants on different types of businesses. Governments can also encourage AI actors to develop self-regulatory mechanisms, such as codes of conduct, voluntary standards and best practices. These can help guide AI actors through the AI life cycle, including for monitoring, reporting, assessing and addressing harmful effects or misuse of AI systems. Finally, governments can also establish and encourage public and private sector oversight mechanisms of AI systems, as appropriate. These could include compliance reviews, audits, conformity assessments and certification schemes.

By coupling flexible, upstream interventions across and between levels, international and national, a new paradigm of governance for online platforms and for AI is beginning to emerge. This new approach strives not only to enable innovation and the benefits that these platforms and actors deliver to society, but also to provide a means for channelling this “creative destruction” toward societal public policy goals.

Authors’ Note

The authors are all members of the OECD Secretariat — follow their work at www.oecd.org/sti and on Twitter (@OECDinnovation). The views and opinions here are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the OECD or its member countries.