During the past year, we’ve seen a marked acceleration of digital transformation momentum among organizations worldwide. Supply chains and customer interactions are becoming increasingly digitized, while digitally enabled products feature in a growing percentage of corporate portfolios. As digital transformation picks up speed, so, too, do investments in cloud and intelligent technologies. Gartner, Inc. predicts that cloud technologies will comprise 14.2 percent of the total global enterprise information technology spending market by 2024, up from 9.1 percent in 2020; further, a recent survey from Gartner, Inc. found that two-thirds of the organizations that responded had either increased or did not decrease spending in artificial intelligence (AI) since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

These converging technology trends — accelerating digitalization accompanied by increasing investment in cloud and AI technologies — are making platform-based business models accessible to a wider range of organizations than ever before. As with the first wave of technology platform companies such as Google, Alibaba, Facebook and Amazon, virtually any company during this new wave has the potential to reinvent itself as a platform — without having to own and maintain proprietary infrastructure.

Technology Platforms versus Platform Business

In a technology context, the term “platform” generally refers to a group of technologies that act as a foundation for the development of other applications, processes or technologies. Apple, Tesla, Amazon, Google and Facebook are all examples of companies that have monetized their technology platforms to support new types of products, services, developer ecosystems and business models.

But platform-based business models are something different, and have deep historic roots. From the agoras and souks of thousands of years ago to companies like Nike and Facebook today, people have shared infrastructure, traded in information and goods, built marketplaces and used both economies of scale and their own ingenuity to invent and grow. Companies in a variety of industries, from manufacturing to automotive to fitness, have embraced the platform model with varying degrees of success.

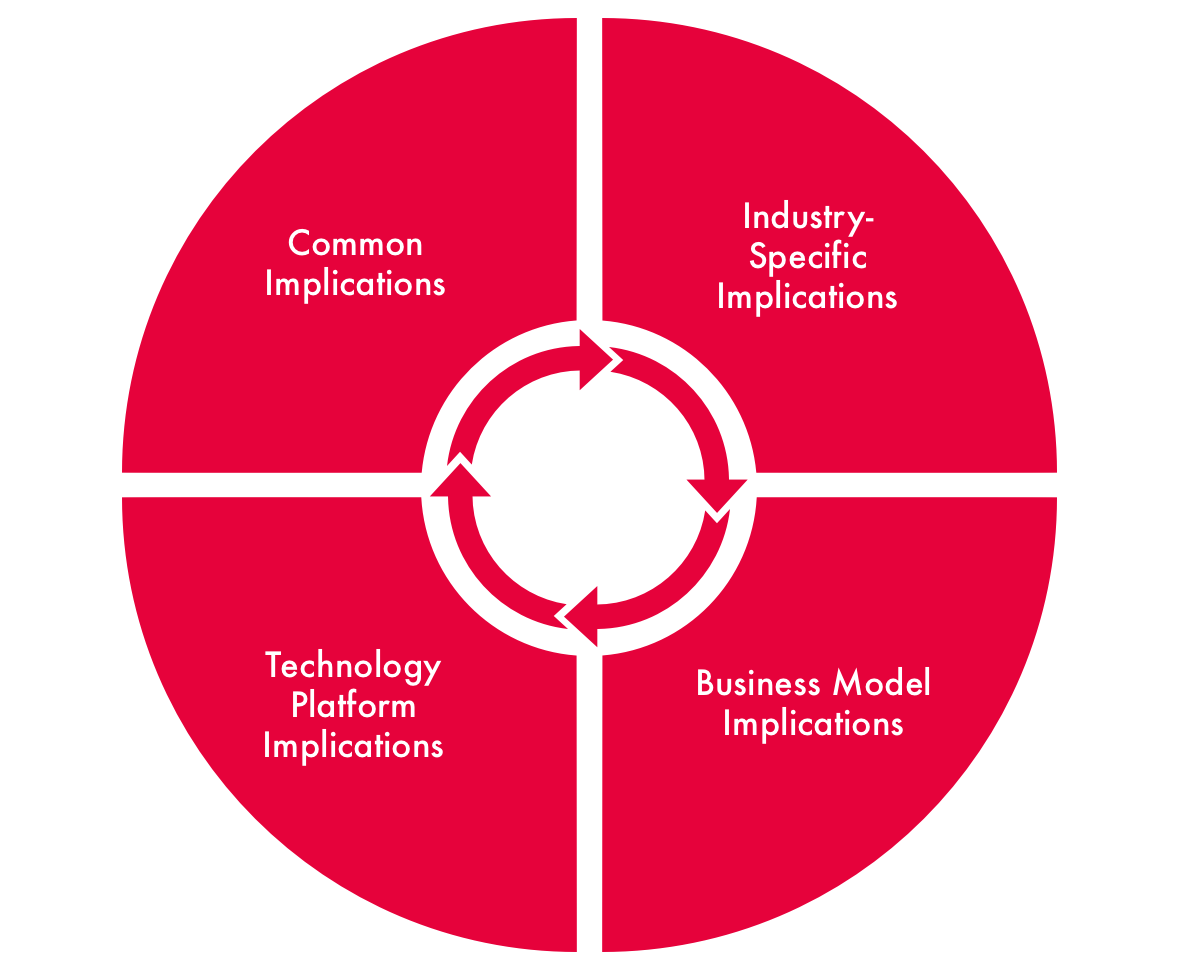

Governance Implications

The shift from product- and service-based to platform-based business creates a new set of platform governance implications — especially when these businesses rely upon shared infrastructure from a small, powerful group of technology providers (Figure 1).

Figure 1: AI Governance Implications of Platform-Based Businesses

Common Implications

Irrespective of the industry or the business model and technology platform being used, some issues — such as cloud security, privacy and ethical data use, bias remediation, model interpretability, accessibility, auditability and use-case review — should be considered table stakes for platform governance. These risks are already well documented by organizations such as the AI Now Institute, Data & Society and the Algorithmic Justice League, and by scholars such as Safiya Umoja Noble, Ruha Benjamin, Cathy O’Neil and others.

Industry-Specific Implications

The industries in which AI is deployed, and the primary use cases it serves, will naturally determine the types and degrees of risk, from health and physical safety to discrimination and human-rights violations. Just as disinformation and hate speech are known risks of social media platforms, fatal accidents are a known risk of automobiles and heavy machinery, whether they are operated by people or by machines. Bias and discrimination are potential risks of any automated system, but they are amplified and pronounced in technologies that learn, whether autonomously or by training, from existing data.

The human impact of intelligent systems can therefore be as relatively trivial as an incorrectly targeted advertisement, or as catastrophic as a lost job or a criminal sentence based on biased data. This means that we cannot rely only on the lessons learned from social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube to frame risks in other industries and for other business models. Rather, we must view industry as another critical dimension of platform governance risk and its mitigation.

Business Model-Specific Implications

As platform-based business models proliferate, it becomes increasingly critical to disambiguate “platform-as-technology” from “platform-as-business model” and delineate the types of platform business models that exist today. The way a particular business makes money and the incentives and disincentives that model sets in motion contextualize the risks and governance implications we must consider.

Business model implications are different from industry implications in that not all companies within an industry make money in the same way. A business that makes money from subscriptions — whether that subscription is to a software platform, a crop tractor or a music service — will have business incentives that are dramatically different from those of a business that makes money by extracting user data to boost engagement. In his book Platform Capitalism, author Nick Srnicek outlines the emerging platform landscape roughly as in Table 1.

Table 1: Types of Platform-Based Businesses

Because each platform type — advertising, cloud, industrial, product, lean — has a distinct set of characteristics, products, services, ways of making money and relative risk, each carries a distinct set of governance implications as well. It’s also critical to note that this depiction is simply a snapshot of business model types that exist today; it does not and cannot account for as-yet-undiscovered sources of business model innovation that will emerge in the future.

Nonetheless, as access to data and intelligent technologies increases, organizations will discover and deploy novel ways of making and saving money — whether by licensing application programming interfaces (APIs) or data or through adaptive reuse of data or components, or by using peer-to-peer models or other methods — which, while promoting efficiency, growth and even sustainability, may also embed and amplify existing biases and other unwanted second-order effects.

Technology Platform Implications

The implications of cloud platforms such as Salesforce, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon and others differ again. A business built on a technology platform with a track record of well-developed data and model governance, audit capability, responsible product development practices and a culture and track record of transparency will likely reduce some risks related to biased data and model transparency, while encouraging (and even enforcing) adoption of those same practices and norms throughout its ecosystem.

For this reason, some platform technology companies, most notably Microsoft and Salesforce, have implemented some or all of the following:

- policies that govern their internal practices for responsible technology development;

- guidance, tools and educational resources for their customers’ responsible use of their technologies; and

- policies (enforced in terms of service) that govern the acceptable use of not only their platforms but also specific technologies, such as face recognition or gait detection.

The above examples are by no means exhaustive, but they represent independent efforts to build organizational capacity for responsible research, technology and product development in the interest of their customers, society as a whole, and, of course, their own reputations and future growth potential.

At the same time, overreliance on a small, well-funded, global group of technology vendors to set the agenda for responsible and ethical use of AI may create a novel set of risks. Many of the features that make these platforms attractive to business, such as simplified data integration and the ability for business users to control the way data is used, generate risks that have the potential to affect all users. Some of these risks — outages, data breaches, denial of service attacks — are common to all technology platforms; others are more specific to AI. Still other risks stem from having such powerful information infrastructure concentrated in only a few companies, a concentration that is especially concerning when those companies also contribute significantly to the funding and research used to frame these issues in the first place.

Putting Platform Business Governance in Context

As we consider the governance implications of platform-based businesses, whether from a common, industry, business model or technology standpoint, it’s immediately evident that the number of variables and the resulting level of complexity are immense, and that even the most granular decisions have global implications. Grounding the risks of platform-based businesses in the context of existing and proposed legal frameworks and governance models can make these challenges more tangible.

One way to identify and contextualize platform business risks is to view them in the context of accepted legal and ethical frameworks such as the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the General Data Protection Regulation and other privacy legislation, and ethical codes, such as the American Medical Association’s Code of Medical Ethics. The past two years have also seen the beginnings of a shift away from defining technology and platform risks as “responsible” and “ethical” business choices and more toward acknowledging how these technologies encode and amplify existing structures of power.

It’s About Power — Not Ethics

Viewing these technologies in the context of the power they exert suggests that digital products and services should be subject to the same consumer protection laws as physical ones, and, similarly, that companies that sell digital products should be required to warrant their products for specific use cases and against others. These approaches seem to be gaining ground. In April 2021, the United States Federal Trade Commission published a statement urging business, in no uncertain terms, to “hold yourself accountable — or be ready for the FTC to do it for you.”

At least in theory, it appears that some corporations are already following this guidance. In 2020, in the wake of widespread protests against police brutality in the United States, Amazon, Microsoft and IBM paused the sale of facial recognition technology to police departments until a national law is in place to govern its use.

As a matter of practice, these companies and others lay out acceptable and unacceptable use cases in their terms of service. Irrespective of existing regulations and the platforms’ own efforts, however, “the governance across the scale of their activities is ad hoc, incomplete and insufficient,” as Robert Fay argues. One of the common arguments against a global platform governance framework, echoed by the platforms themselves, is that it is in everyone’s best interests to identify and remediate any significant adverse consequences of their technologies, products and services. But independent (and arguably opportunistic) choices by large and powerful companies cannot replace the safeguards of legal frameworks developed to apply consumer protection principles consistently and in the public interest — even if, as some companies argue — their intentions are to promote a global good.

Nor, Fay contends, is the moment in which we find ourselves entirely unprecedented. In the 1990s and early 2000s, unconstrained growth in the service of a “global good” led to drastic financial and social impact in the form of a global financial crisis. As a result, the Group of Twenty mandated the creation of the Financial Stability Board, a body that would “coordinat[e] national financial authorities and international standard-setting bodies as they work toward developing strong regulatory, supervisory and other financial sector policies.” Fay likewise makes the case for a digital stability board, which could help to coordinate platform governance efforts among member nations.

Designing a Policy Agenda for Platform Business

Given that many of the issues related to platform business are known risks of technology platforms powered by intelligent technologies (and are therefore ingrained risks for any platform business), the following four actions should be at the top of the policy agenda for any government or corporation, as they have tremendous potential to affect the health, livelihood, freedoms, access and other rights of the people they purport to serve.

Require Platform Technologies to Adopt Explainability and Interpretability Standards

The ability for algorithms or other systems to provide and justify the rationale for their conclusions should be fundamental to any system that has the power to affect human life. Whether it is the reason for denying a loan, grading a student, identifying a suspect in a criminal case or serving a recruiting ad, algorithmic systems must be transparent and clear. The need is particularly critical when these systems are used for applications that have been identified as high-risk, as described in the European Commission’s newly proposed regulation laying down harmonized rules on AI (Artificial Intelligence Act).

Require Bias Remediation and Auditing for High-Risk Applications

Platform businesses must also have the ability to, first, identify and remediate and, second, audit, monitor and disclose issues in data sets and data models related to bias and discrimination. These issues might include disparate outcomes related to gender, race, age, economic status, disability, religion or other protected status. Companies such as Microsoft, Salesforce, Google and others, as well as computer scientists and data scientists at universities around the world, have published hundreds, if not thousands, of papers on these topics.

While platform technology companies have instituted research and product development processes — including impact assessments, model cards, data sheets for data sets and other tools — intended to educate data scientists, model builders, engineers and product managers about potential limitations or impacts of the data that they use, these practices are still fairly limited in scope and entirely voluntary. Further, they lack not only common standards but also a common framework for implementation.

Audit is another area that, while promising, is also fraught with potential conflict. Companies such as O’Neil Risk Consulting and Algorithmic Auditing, founded by the author of Weapons of Math Destruction, Cathy O’Neil, provide algorithmic audit and other services intended to help companies better understand and remediate data and model issues related to discriminatory outcomes. Unlike, for example, audits of financial statements, algorithmic audit services are as yet entirely voluntary, lack oversight by any type of governing board, and do not carry disclosure requirements or penalties. As a result, no matter how thorough the analysis or comprehensive the results, these types of services are vulnerable to manipulation or exploitation by their customers for “ethics-washing” purposes.

Document and Enforce Unacceptable Uses of Intelligent and Platform Technologies

While all technology platforms require customers or users to comply with their terms of service agreements, the ability to enforce which uses of their technologies are acceptable versus unacceptable is inconsistent and limited. Some companies may authorize the use of facial recognition, gait detection or biometric data for virtually any purpose, while others may restrict the circumstances under which these technologies may be used. Complicating this further is the fact that, for privacy reasons, some technology platform companies have no access to their customers’ data, so they may not even be aware when their platform is used for prohibited or unintended purposes.

Institute Whistle-Blower Protections for Technology Workers

The ability of employees of corporations or start-ups to receive whistle-blower protections if they identify adverse effects of algorithmic systems or decisions is unclear. In March 2021, prompted by the effective firing of Ethical AI co-leads Timnit Gebru and Margaret Mitchell, the group Google Walkout for Real Change urged the United States Congress to strengthen whistle-blower protections for technology workers, stating that “the existing legal infrastructure for whistleblowing at corporations developing technologies is wholly insufficient.”

Conclusion

The use of Facebook as a tool for ethnic cleansing in Myanmar in 2017 and 2018, the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal, and the 2019 livestreaming on Facebook of the Christchurch killings are just a few examples of the global impact of product decisions made by a relatively tiny number of people at social media platform companies who, irrespective of intention, were neither required, encouraged nor trained to detect and prevent such occurrences from happening. Now that platform technologies are generally available, and platform businesses are using them in increasingly novel ways, the risks of these tiny decisions are compounding at an alarming rate.

Therefore, to address not only current but future platform governance risks, we must broaden our understanding of platforms beyond social media sites to other types of business platforms, examine those risks in context, and approach governance in a way that accounts not only for the technologies themselves, but also for the disparate impacts among industries and business models.

This is a time-sensitive issue. The complexity of data- and algorithm-based decision making, the speed of technology adoption, and the lack of clear and durable governance frameworks have created a climate in which there is little oversight and much experimentation. Large technology companies — for a range of reasons — are trying to fill the policy void, creating the potential for a kind of demilitarized zone for AI, one in which neither established laws nor corporate policy hold sway. As platform-based business models proliferate, it becomes critical for policy makers to anticipate their human impacts and to craft policies to address them in such a way as to centre the welfare, rights and safety of the people they serve.