ny discussion of post-pandemic reform in Canada’s security and intelligence (S&I) complex — and in this I include public health emergencies — necessarily operates within the confines of the very tight strategic box in which Canada finds itself.

Analytically, it is simply inaccurate to call today’s Canada an “ally” of the United States. We are, in law, strictly speaking, a vassal state of America. The Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) is clear in this regard. The agreement requires Canada to seek permission from the United States in order to pursue advanced economic relations with major countries such as China. (I discuss Canada’s intellectual and information-space vassalization below.)

Read strategically rather than textually, the practical result of article 32.10 of CUSMA is to place a hard cap on our ability to have deeper relations, in all respects (not just economic), not just with China but, indeed, with any major twenty-first-century power — China, Russia, India, Turkey, Iran and so forth — without prior initiative or approbation from Washington. Indeed, the threat of an American veto on any such Canadian deepening, whatever its intensity, now hovers over Canadian options in perpetuity. This is perfectly understood by all major capitals in the world, as is the political difficulty of Canada ever extracting itself from this straitjacket.

Analytically, it is simply inaccurate to call today’s Canada an “ally” of the United States.

If Canada is formally a vassal state, then the country can have no foreign policy in any substantial sense — that is, exempting transactions of a largely marginal character in the international system. Our S&I arrangements similarly assume a largely tactical character, dealing mostly with internal improvements of law, machinery, processes and talent.

Yet the post-COVID-19 structural reality of Canada makes the vassal structure of Canadian planning extremely awkward for purposes of national security and Canadian interests, for at least four cardinal reasons:

- The US border is quasi-closed for the foreseeable future, and may be regularly closed in future when emergencies arise, making a “theory of the (Canada-US) border” far too limited and simplistic an intellectual framework for Canadian strategic decision making.

- The United States will not necessarily wish or be able to defend Canada in all strategic circumstances, and may even attack or otherwise undermine key Canadian interests in certain cases.

- Two new effective Canadian borders (discussed below) — with China to the west and Russia to the north — now make plain that Canada’s strategic geography and interests are not sufficiently captured within a vassal state or American border framework.

- American analytics or commentary on these new borders and many other international questions — commentary on which Canada typically relies and to which we commonly defer — is often not top-of-class or is otherwise reflective of strictly American interests, priorities and narratives.

Canada’s strategic and S&I options in the coming years are therefore fairly dyadic: either consolidate the vassal position (as per the current policy momentum), or attempt, over time and not without considerable work and difficulty, to exit this position in order to reckon with these four dynamics as we Canadians see fit, the end result of which, as I explain below, could mean that Canada itself becomes a great power this century.

I propose five moves in support of the second variant.

Move 1: Create and Control a Properly Canadian Information and Analytical Space

If Canadian vassalization exists in law, then the enabling intellectual-psychological conditions of national vassalization run far deeper. Ours is a country that today has no coherent information space in which to properly understand and analyze our own (strategic) circumstances, to debate and formulate policy positions and proposals without interruption, displacement or complete cannibalization by topics, interests and algorithms run by far larger outside players.

If the population difference between the United States and Canada is roughly of a 10:1 ratio, then the ratio of American to Canadian books in Canada’s English-language bookstores is of a 50:1 order. Online, the ratio of American to Canadian websites is likely of a 1,000:1 order. And on social media, where much of the political and policy debates happen increasingly, the ratio of American active Twitter users (more than 60 million) is 7:1 that of active Canadian users (more than 8 million). The combination of American invention, control and moderation of the Twitter algorithm (and most other leading social media algorithms); the fact that nearly all of the world’s leading Twitter users (by followership) are American; and that there is no language barrier, in English, between American and Canadian Twitter users, means that the retweet (or repost) rate of American tweets (and posts) versus Canadian tweets (and posts) is at least in the order of one million to one.

If most Canadian decision makers — political and policy alike — are on Twitter actively, their Twitter feeds are, by definition, entirely colonized by American information, analytics, framing and discourses. Any Canadian thesis, counter thesis or bit of news risks being overwhelmed, distorted, confused, vitiated or, if there is intent, undermined by American control and dominance of the very platform where Canada does, with ever-growing preponderance, much of its public policy thinking.

Yet this reality flies in the face of the basic strategic requirement that Canada, should it wish to devassalize, be able to “think for itself,” about itself. This means at least the following:

- deep (aggressive) regulation of American and all foreign social media platforms, not just on privacy grounds but, more importantly, to ensure that Canadian users and stories receive privilege in Canada; and

- creation of world-class Canadian (led and controlled) social media and news platforms (in English, French and Indigenous languages, in the online, television, radio and print media), and the subsidization of leading Canadian journalism, analysts and bureaus on a significant scale across all of these platforms.

Below, I discuss a national languages strategy as an essential element in Canada being able to think for itself (not just in English), and also in the context of a far larger population over time (also an essential element of strategic devassalization).

Move 2: Operate from the Correct Mental Map

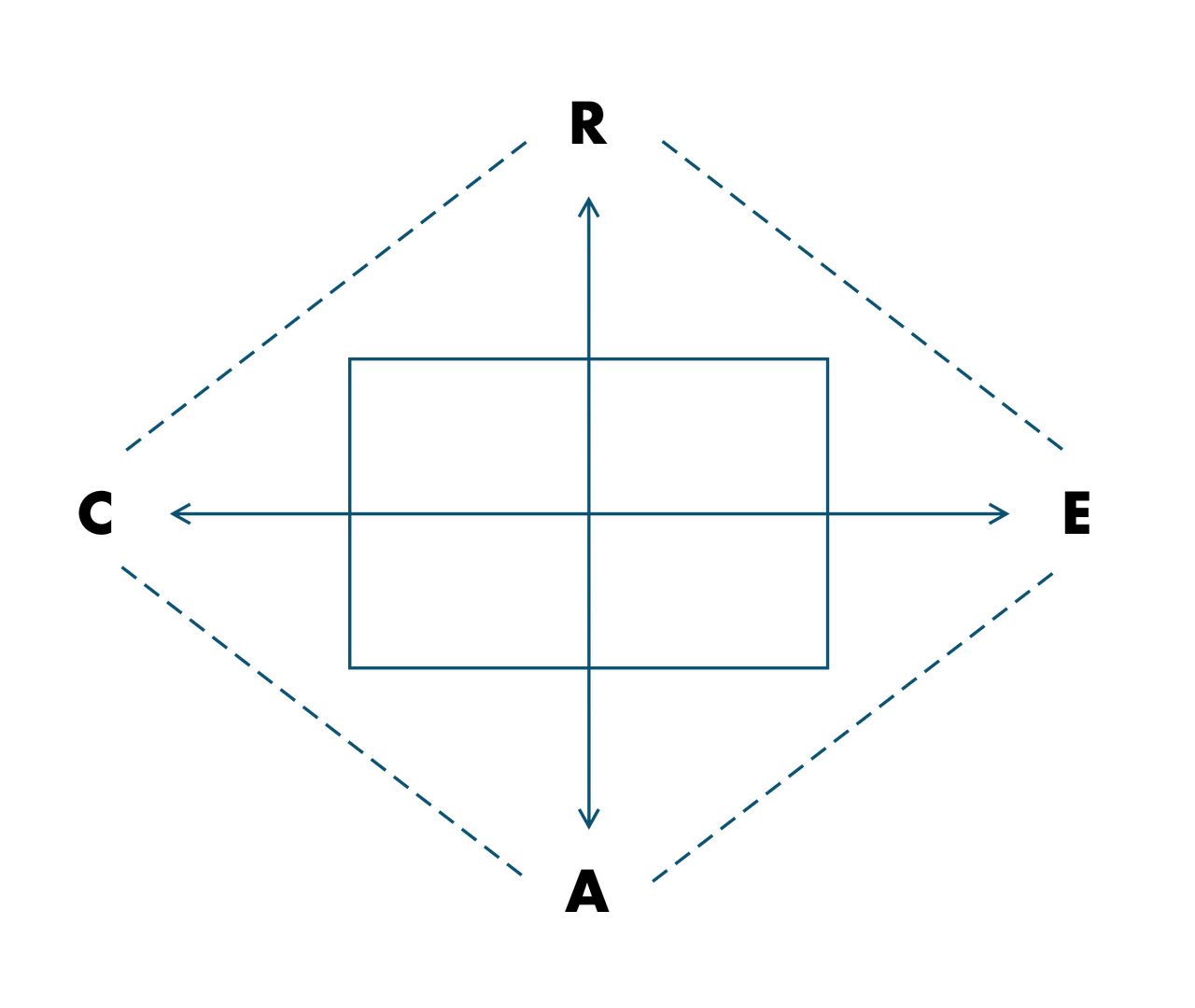

Canada has four relevant borders this century — not just the American one — as traditionally imagined in the mental map of Canadian decision makers. I call these borders “ACRE” (America to the south; China to the west; Russia to the north, across our Arctic; and Europe to the east) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Canada’s Border Neighbours

Canada will live or die by this four-point game, stretched and pulled by the competing gravities of its huge neighbours (all nuclear), or otherwise pressed or even crushed by their power plays across our geography and political and information space. Indeed, I count 15 different combinations (vectors) of strategic pressures, pulls and complexity for us to manage this century: America (A), China (C), Russia (R), Europe (E), AC, AR, AE, CR, CE, RE as well as ACR, ARE, ACE, CRE and ACRE.

If the America and Europe vectors are deeply familiar to Canada’s strategic and historical imagination, then the China and Russia vectors are almost entirely new. How so? Answer: Canada has not known an extremely powerful, sophisticated, largely stable China for nearly all of its modern existence. The nineteenth-century Opium Wars that destabilized China ended just prior to Confederation, and the century and a half that it took China to restabilize — strategically, economically and intellectually — coincides almost exactly with the 153 years of Canada’s modern existence.

Canada, therefore, fundamentally, in its decision-making psyche and in the public consciousness more generally, still imagines China to be systemically backward, ethically primitive and, critically, geographically very distant from us.

This is a huge mistake. For, despite its pathologies and hysteria around the coronavirus pandemic, China is today extremely sophisticated systemically and, critically, far closer to Canada than we realize (that is, Beijing is closer to Whitehorse, Yukon, than it is to Sydney, Australia). In other words, Canada is very much “in Asia” (even more than Australia), and China is our de facto neighbour.

As for Russia, it too, properly understood, is entirely “new” to Canada’s strategic psychology. Not only is Russia, in its post-Soviet form, a relatively new state (less than 30 years old) but it is, in the most relevant sense for Canada, not to the east of Europe and Ukraine, as we typically imagine it, but now in direct juxtaposition with our northern flank in virtue of the rapidly melting Arctic. This northern Russian border, as with our western Chinese (or Asian) border, is largely foreign to the mental map of a country that, from at least the publication of the 2004 National Security Policy (of which I was a co-author), has reduced most of its foreign policy to a theory of the American border.

Canada’s vassalization through CUSMA occurred with virtually no debate of strategic moment in society or Parliament, precisely because we were operating from a mental map that reduced strategy to a border equation, in ignorance of our proper strategic circumstances, whereas the Americans, as a term-setting great power, were operating from a far larger, more global mental map. Needless to say, devassalization invariably means that Canada will have to reverse the CUSMA mistake and reset the American relationship in the context of the 15-combination game that we will need to master in the coming decades.

Move 3: Know and Press the Factors of Canadian Power

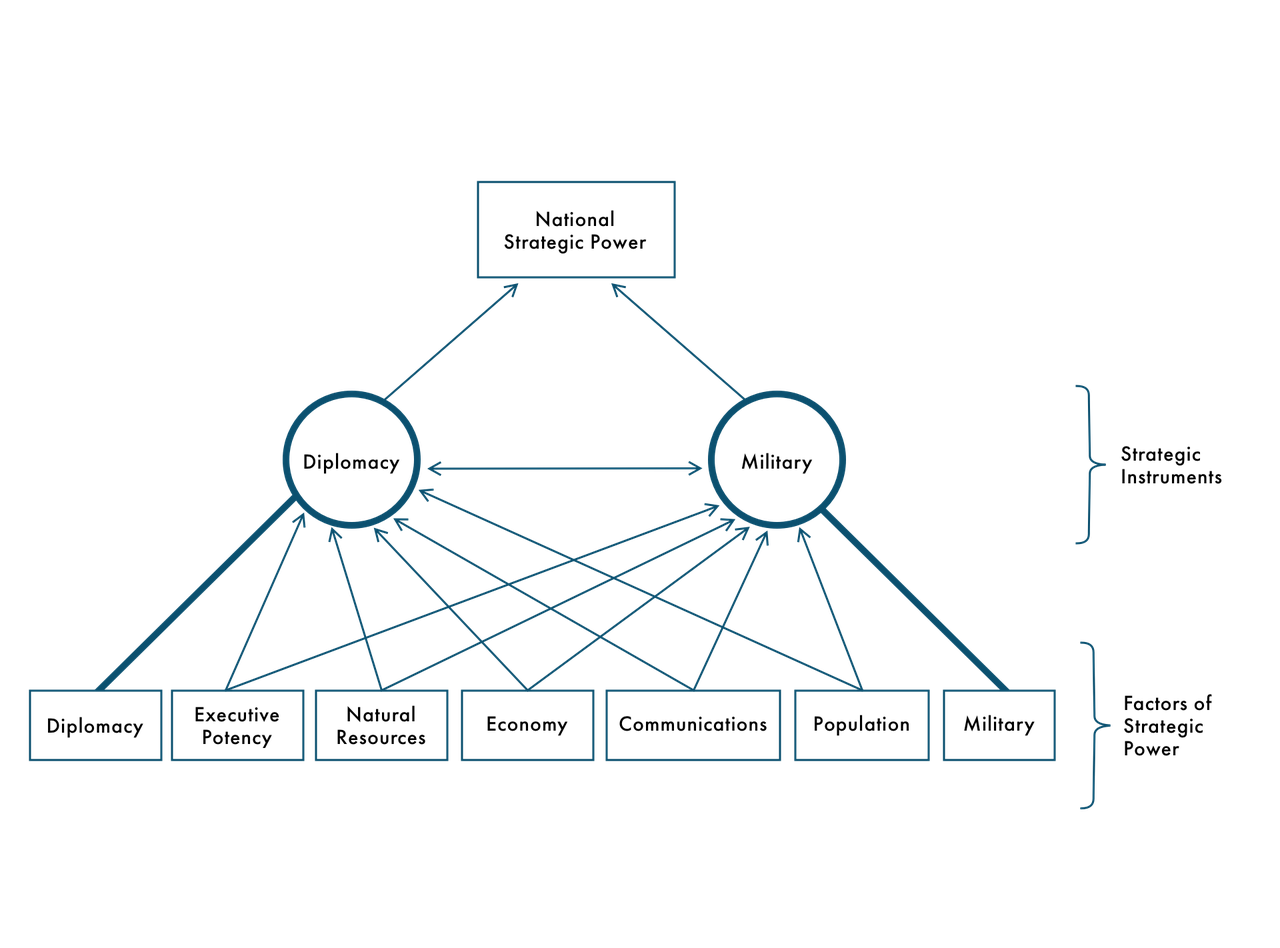

Most Canadian strategic and S&I debates work at the paper-tip level of fundamental power (as with a boxer who punches with the fist only, forgetting the fundamental role of their torso and legs in their potency, or lack thereof). They neglect the key role of “factors of power” in underpinning, supporting or, in the opposite case, compromising the magnitude of Canadian strategic power or action. Some of these factors of power are population size (as well as talent and distribution), territory, natural resources, government, economy, transportation and communications, intelligence, the military and diplomacy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Factors of Power

Despite Canada’s vassal state status, we in fact already have all the factors of power in place to become a proper great power, save two: a sufficiently large population across our huge territory and a term-setting mentality. (Factors of power such as the economy and the size of Canada’s intelligence, defence and diplomatic capabilities, aside from the recommended changes I describe below, will increase in significant correlation with the increase in Canada’s demographic weight.)

Over the last decade, I have been driving a growing national debate for a Canada with a population of 100 million by the year 2100, building on my 2010 Global Brief article entitled “Canada — Population 100 Million.” Let me stress, as I have many times before, that the 100 million quantum is symbolic — we might speak of a population of 85 million (as very recently advocated by former Prime Minister Brian Mulroney) or even 120 million. Larger is critical over time, and so too is the momentum of population growth — that is, the migration of the national strategic imagination into understanding that Canada is headed (kinetically, over the coming decades) for a larger telos.

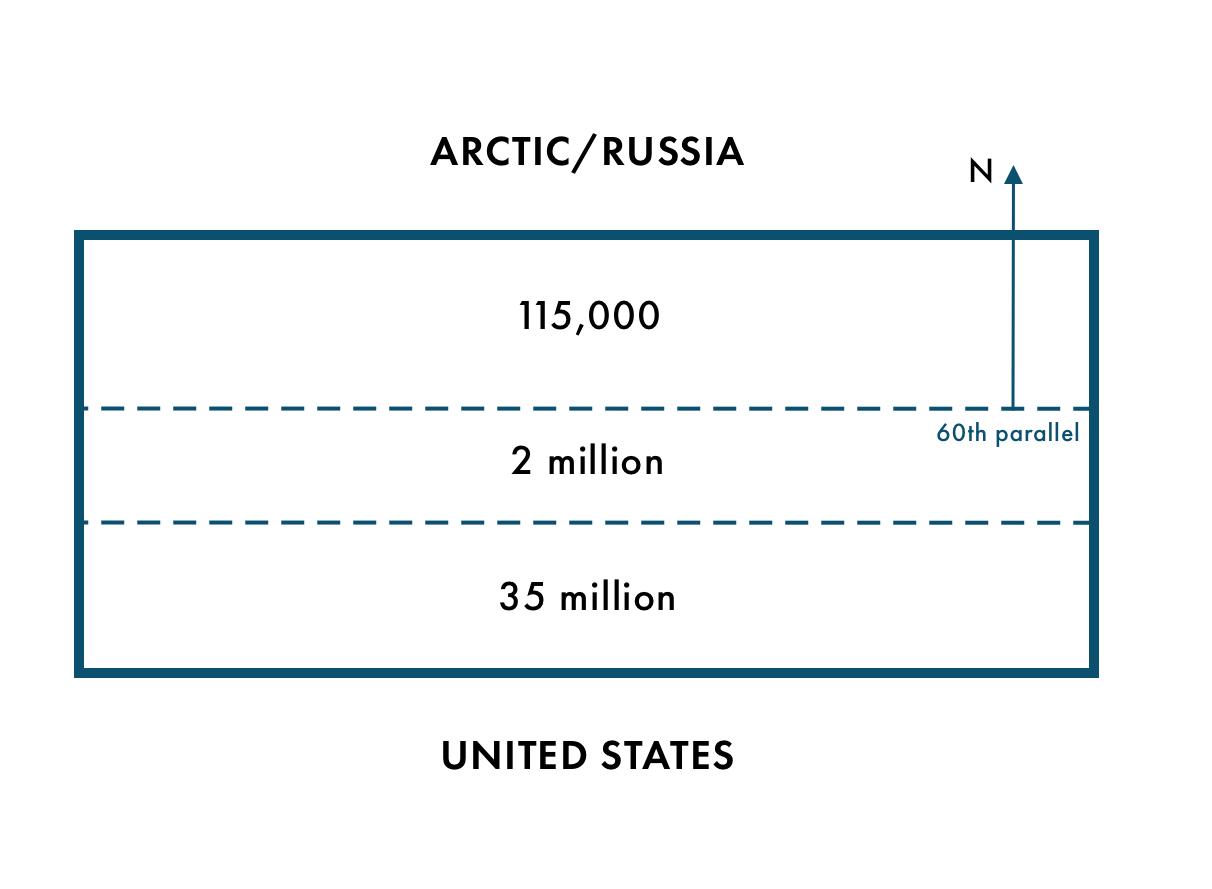

In the Arctic alone, given climate change and the rise of the “R” vector, Canada will need many more millions of people north of 60 if we are to master our strategic circumstances. We currently have a population of 115,000 across the three northern territories, equivalent to the demography of Ajax, Ontario, for a territory the size of the European Union (see Figure 3). The Russians, by juxtaposition, have more than two million people in their Arctic, and more than 50 million in their supporting northern regions.

Figure 3: Population Distribution North of 60

As for the term-setting mentality, that is a function of education and political leadership and pressure. After all, a Canadian population of 100 million could still, in the absence of a term-setting mentality, be vassalized or self-vassalize, although a term-setting mentality without a much larger Canadian population as an objective factor of power would have difficulty advancing key Canadian strategic and S&I imperatives. On the other hand, a Canada at 100 million that masters its four-point strategic game, with its 15 combinations of pulls and pressures from our great-power neighbours, could itself emerge a great power by sheer dint of having survived this complex game. (En passant, if it survives that long, a Canada at 100 million by century’s end would very likely be larger than any country in Europe as well as contemporaneous giants such as Japan and Russia, assuming Russia itself survives in its current form.)

Move 4: The Plumbing, Machinery and Relationships

A Canadian S&I community that “thinks for itself” and is surrounded by great powers must operate at an appropriately significant scale and with substantial independent capabilities. This means a manifestly independent human intelligence capability (in my view, deployed eventually out of the Department of National Defence [DND], as with the birth of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service). We must also triple the quantum of linguists and top area and disciplinary analysts at the Privy Council Office/Intelligence Assessment Secretariat, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, the DND, the Communications Security Establishment and, yes, the Public Health Agency of Canada, and original research and contributions to the development of a properly Canadian school of strategy, with its own mentality, doctrine, vocabulary and world-beating talent. (I have long argued for a national languages strategy, starting in the educational systems, in support of such talent creation, but also to blunt Canadian submersion in the American-dominated information space, in English, in North America. In this sense, a Canadian national languages strategy would aim for full French-English bilingualism across its entire population, even at 100 million, and for most Canadians to have fluency in a third tongue, Indigenous or foreign, on top of that.)

While the United States and Five Eyes (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States) S&I relationship may (or may not) remain primus inter pares, a Canada that thinks for itself will need and want to profit from professional working relationships with all of the major powers of the world, and most of the second-order ones as well, whether they are “like-minded” or, as in most cases, not. The global coronavirus emergency will have disabused us of the notion that only democracies generate good, legitimate or “moral” intelligence or frameworks, and should commend to us far great promiscuity in our search for the best information possible to defend or advance Canadian interests.

In terms of worldwide embassy presence, outside of the United States and the ACRE framework, Canada’s diplomatic representation and therefore relationships are extremely limited. In the former Soviet space, we have embassies in only six of the 15 former Soviet states. In the Middle East, we have embassies in nine of the 16 countries. And in Africa, we have embassies in slightly more than half of the 54 states. We need our own embassies, not co-located, in every country in the world (with many additional consulates spread within key regions), viewing each relationship as an objective entry point into any number of desired outcomes, including significant learning opportunities, from like-minded and non-like-minded countries alike, with diplomatic reporting committed not just to reporting local situations and trends but, indeed, to suggesting what Canada can or must “learn” or even copy in systems and policy terms (including in respect of health, public health and pandemic management) from every corner of the globe.

Move 5: To What Ends?

A policy agenda for devassalization, on the logic I have commended above, is about means, not ends. As such, it reverses conventional Western and Canadian strategic logic, which posits the need to establish end goals and objectives prior to the delineation of the various means and instruments to be deployed in the realization of such ends.

What would a devassalized Canada do with its power, and to what ends would it apply its S&I assets and capabilities? Answer: It would behave as a term-setting country — one able to secure its own defence and national interests, but also able to set the term, rules and logic for many global debates in respect of the broader human condition.

But let me add, critically, that Canada does not yet know how a term-setting country (or even a great power) thinks or how to assume term-setting or great-power positions. As such, we do not yet know the targeted national or international “ends” that will accrue to a more capacious national strategic imagination. These ends will begin to come into sharper relief as we put in place the various means posited in this essay. We cannot know them in the abstract as a vassal, but they may well surprise us when we look back, a few decades down the road, from the devassalized posture.