Indigenous communities tend to have a special relationship with their lands. To them, land is a source of both knowledge and strength. In some Indigenous cultures, land is not just an abstraction but includes “people and animals, rocks and trees, lakes and rivers” such that “humans held certain obligations to the land, animals, plants, and lakes in much the same way that we hold obligations to other people.” Unfortunately, corporations don’t usually understand or fully appreciate this relationship. And while such business activities offer opportunities for economic development, they can negatively impact Indigenous culture and the environment, but that doesn’t need to be the case. Corporations could work collaboratively with Indigenous communities, adopt best business practices, facilitate solutions and mitigate environmental challenges. These collaborations could be immensely helpful in Canada’s domestic implementation of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Understanding UNDRIP

Through its text, UNDRIP advances the protection of Indigenous lands in a variety of ways. The declaration is especially sensitive to projects that could lead to land, territorial and resource dispossession or to the forcible removal of Indigenous peoples from land and territories. Corporations may precipitate conflict with Indigenous communities if their corporate activities entail developmental projects on Indigenous lands

The duty to implement provisions of the declaration rests on state actors through guidance to other actors, including corporations. Although UNDRIP does not refer to corporations in its text, corporations could nevertheless contribute to UNDRIP implementation in domestic legal contexts. As John Ruggie noted in his 2013 book, Just Business: Multinational Corporations and Human Rights, the core of the corporate human rights challenge is that “globally operating firms are not regulated globally….Instead, each of their component entities is subject to the individual jurisdiction in which it operates.” While protecting the rights of Indigenous peoples and their communities is of concern to international law, real implementation happens mostly at the domestic level. When Ruggie’s “protect, respect and remedy” framework is applied in the UNDRIP context, it means corporations should respect human rights. If corporations conduct their business on Indigenous lands and respect human rights of Indigenous peoples in the process, then they would be contributing to effective UNDRIP implementation.

UNDRIP states that Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources. The declaration also provides that states shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the Indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, in particular in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources. Further, UNDRIP declares that states should provide effective mechanisms for just and fair redress for any such activities, and take appropriate measures to mitigate adverse environmental, economic, social, cultural or spiritual impacts.

The Canadian Government’s Role in Implementing UNDRIP

In May 2016, Canada’s Minister of Indigenous Affairs Carolyn Bennett told the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues at the United Nations that Canada intended “to adopt and implement [UNDRIP] in accordance with the Canadian Constitution.”

It would seem, however, that what it means to “adopt and implement” UNDRIP needs to be further clarified. According to a report by the Shareholders Association for Research and Education (SHARE), Canadian companies are often “waiting for direction from the federal government before making a commitment to adopt UNDRIP into their practices.” It may be the case that corporations with this disposition desire some degree of certainty in terms of their legal obligations going forward. However, as SHARE suggests, “Nothing is barring companies in Canada from proactively adopting UNDRIP as a guide to business conduct and they may be missing out on opportunities by failing to do so.”

Until very recently, Canada’s Parliament discussed two bills that could have significantly impacted the relationship between corporations and the Indigenous communities in which they conduct their business. The first (which could not be passed before the 2019 session of Parliament ended) should have required Canada’s federal government to consider UNDRIP before bringing in new laws and examining existing ones. The second (which was eventually passed after substantial amendments) alters federal environmental assessment processes to include a broad range of social impacts that could be of concern to Indigenous communities. These efforts are in line with Ruggie’s framework — Canada is trying to fulfill its duty to protect human rights by developing laws and policies consistent with UNDRIP.

Corporations’ Role in Implementing UNDRIP

Corporations have a duty to comply with all applicable laws and not interfere with human rights through their business activities. Both bills mentioned above have expansive duty-to-consult elements in relation to commencing business activities in Indigenous communities which, in a way, would contribute to fulfilling the free, prior and informed consent requirements contained in article 32 of UNDRIP. Such legislation is by no means the only way for corporations to better integrate UNDRIP into their activities.

Corporations can decide voluntarily to integrate UNDRIP in their practices. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, for example, acknowledges that “the resource extraction industries…have an important role in contributing to the economic and social sustainability of Indigenous peoples in Canada,” and that “government has the primary responsibility. It is important for government to fulfill its duty in reconciliation and not pass this responsibility or cost on to industry.” Canada’s largest natural gas distribution provider, Enbridge, is among the few Canadian corporations that recognize the importance of UNDRIP within the context of existing Canadian law and the commitments that the Canadian government has made to protect the rights of Indigenous peoples. How (and whether) these corporate undertakings are implemented in practice is less clear-cut. It seems, therefore, that more education, awareness and training about UNDRIP by and for corporations would be a good first step even as the government develops laws and policies to integrate the declaration.

To address environmental challenges and achieve UNDRIP goals, there is a need for corporations to strengthen existing methods of engagement with Indigenous communities and to develop new ones. As a component of the education and awareness training suggested above, Canadian corporations should support the federal bills intended to implement UNDRIP to the extent that they address issues crucial to safeguarding the natural environment in Indigenous communities. Notwithstanding the widely reported corporate opposition to the bills, the author submits that it would make good business sense to support the bills as part of the larger goal of reconciliation and to earn the needed approval of Indigenous communities for a “license to operate” on their traditional lands.

As SHARE warns, “Companies that fail to operate in a way that respects an international law standard like UNDRIP expose themselves to risks of reputational damage, regulatory intervention, litigation, project delays and disruptions, shutdowns and financial loss.” In fact, rather than opposition, Canadian corporations could go a step further by consulting with Indigenous communities and agreeing on complementary environmental objectives. Such socially responsible corporate behaviour promotes reconciliation and also offers competitive advantage to the corporations practising them.

As John Sandlos and Arn Keeling suggested in a 2016 article, Canadian corporations should consider an expanded understanding and use of traditional knowledge both in environmental impact assessments and remediation, for example, in the context of reclaiming and restoring former industrial sites. The Mackenzie Valley Environmental Impact Review Board’s Giant Mine clean-up efforts in the Northwest Territories is an instance in which traditional environmental remediation knowledge could have been useful. The law relevant to the board’s 1998 toxic arsenic trioxide remediation plan mandated community consultation and consideration of the impact on Aboriginal lands and communities and required that traditional knowledge be incorporated into the environmental assessment and evaluation process. Although the Giant Mine clean-up exercise concerned a situation where government intended to enforce environmental impact assessment standards, Indigenous environmental knowledge should also be considered in situations where corporations are solely responsible for cleaning up the environmental damage resulting from their business activities. In such situations, Indigenous environmental knowledge could be just as helpful to corporations as it would be to government regulators.

Corporations and Indigenous communities could work together to reform the environmental components of impact and benefit agreements (IBAs) that are often negotiated between natural resource developers and Indigenous communities. These agreements typically serve two purposes. First, according to Courtney Fidler and Michael Hitch, they “accommodate aboriginal interests by ensuring that benefits and opportunities flow to the community.” Second, they “address social risk factors within the community such as adverse socio-economic and biophysical effects of rapid resource development.” While both goals are harmonious with article 32 of UNDRIP, the environmental elements of IBAs are often weakly articulated and implemented. This could be due to environmental monitoring boards acting as oversight mechanisms rather than as active participants, or, as Fidler and Hitch put it, “traditional knowledge [necessary in IBAs] and its culturally compatible notions of social development [being] subverted by key capitalist indicators of benefits.” As well, current criticisms of IBAs — for example, that they are mostly confidential and that Indigenous communities have no power to stop projects that they do not consent to — should also be addressed.

Finally, Canadian corporations in relevant sectors could partner with Indigenous communities that are moving forward with renewable energy initiatives within their territories. There is opportunity for corporations to tap into this development, which has been described as a potential vehicle for Indigenous reconciliation efforts. Through this process, corporations and Indigenous communities alike could benefit in a few ways: Indigenous communities would be able achieve greater energy autonomy, establish more reliable energy systems and reap the long-term financial benefits that clean energy can provide. Further, corporate participation could help to better address specific climate change impacts in Indigenous communities.

Conclusion

As with other international law standard-setting documents, the effectiveness of UNDRIP will depend on its integration into domestic legal regimes. Canadian corporations have long recognized that they have a role to play in implementing UNDRIP in Canada, but they claim to be waiting on the government to provide further guidance. While awaiting this guidance, corporations should take proactive, collaborative measures to integrate UNDRIP into their business practices, address environmental challenges and support reconciliation.

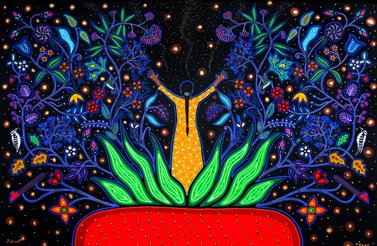

About the artist: Kenojuak Ashevak is regarded as one of the most notable Indigenous pioneers in modern Inuit art. She travelled all over the world as an ambassador for Inuit art. Her enthusiasm and devotion to her work has provided inspiration to generations of artists in Cape Dorset.