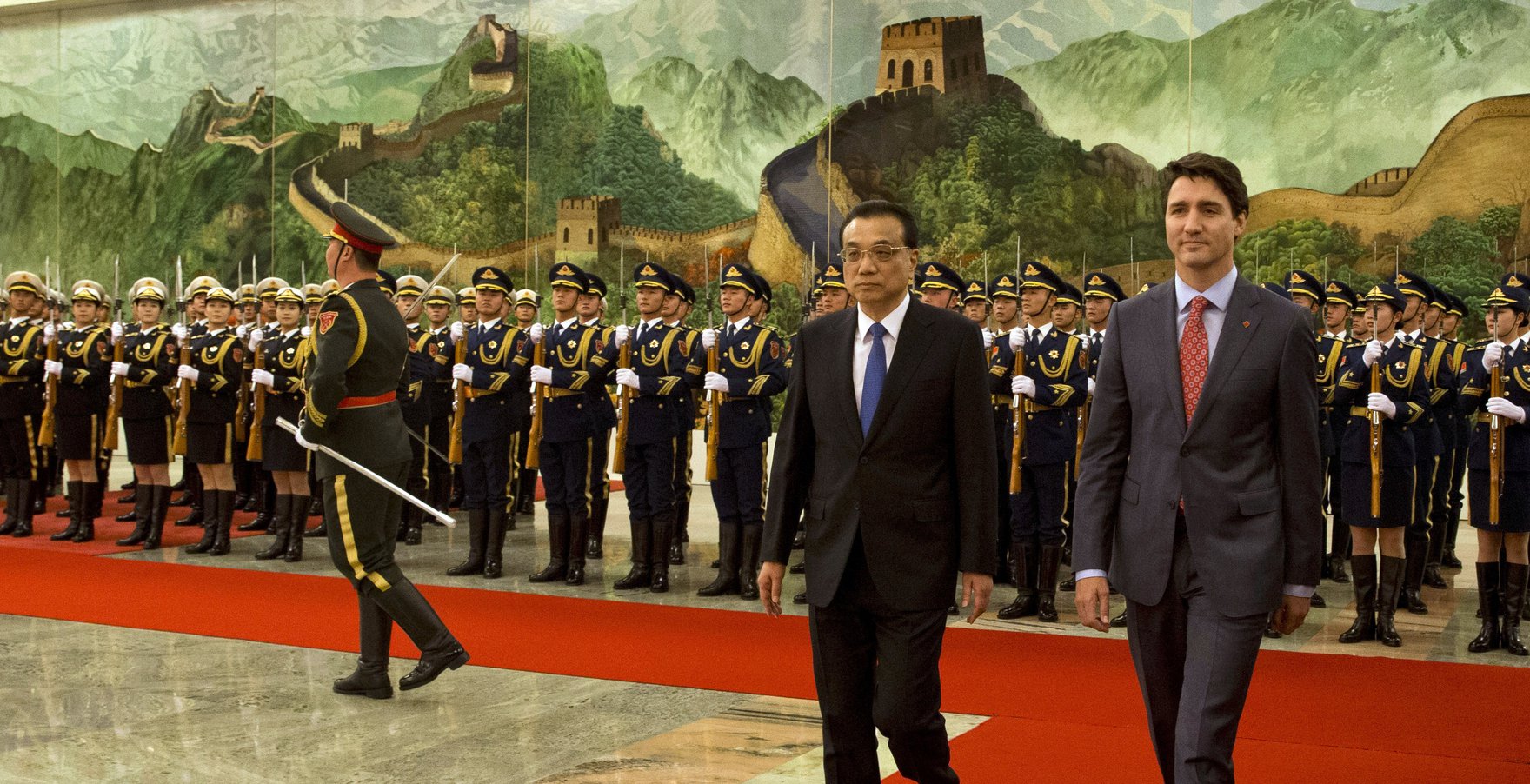

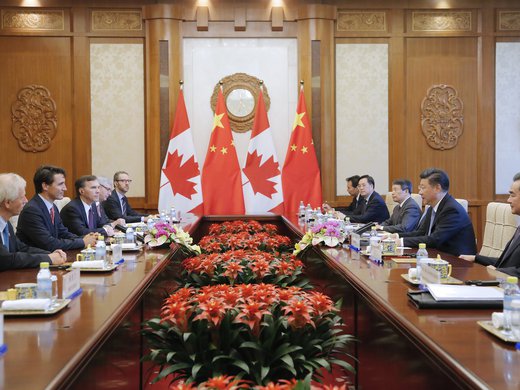

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s December 4 statement from Beijing didn’t include the widely expected announcement of an official start to the negotiation of a free trade deal with China. He specified instead that both countries will continue “exploratory discussions” around free trade, and highlighted Canada’s desire to pursue trade that “reflects Canadian values.” But Canada’s progressive trade agenda, with a heavy emphasis on the environment, gender and labour standards, doesn’t fit seamlessly into a trade relationship with China.

Three CIGI fellows commented on the nature of Canada-China trade, the possibility of imposing progressive trade measures in China, and how Trudeau’s ambitious trade goals fit into his Group of Seven (G7) presidency.

Human Rights the Biggest Obstacle

China has two main concerns in trade talks with Canada: the symbolic significance of negotiating trade with a Western, industrial, developed G7 economy, and gaining access to Canada’s agricultural products and natural resources — in particular the oil sands. Compared to these two major issues, the progressive trade agenda is not important for China. That said, it will discuss progressive trade if Canada insists.

Both countries have incentive to cooperate on some areas of the progressive trade agenda — such as the promotion of environmental protection and sustainable development. Labour standards may get some attention, but gender equality and the advancement of women’s economic empowerment in general will not be an issue for China.

There are some “hard” human rights issues that are related to China’s core interests, such as the lack of freedom of speech or assembly, limited religious freedom and the poor treatment of political dissidents. China will not give any concession on these issues. The rights to freedom of association and collective bargaining under the category of labour rights, by the same token, will not be on China’s list for discussion.

Canada doesn’t have to sacrifice most of its progressive trade measures to negotiate a decent trade deal with China. But the “hard” human rights issues, along with any proposed intervention in China’s internal affairs, could be the biggest obstacle for both countries in discussing trade.

— Alex He, CIGI Research Fellow

Some Canadians Stand to Lose

Canada should and can promote a progressive trade agenda with China. But it needs to do so in a pragmatic way — the Canadian government should be prepared to adopt progressive policies at home to ensure the benefits of trade liberalization are widely shared.

A progressive trade agenda includes environmental standards, labour protection and gender equality, among other things. These are inherently valuable goals. However, China is not likely to accept a Canadian framework as a condition for starting trade negotiations. It would be more practical for Canada to begin trade talks with China based on mutual economic benefits and push for its progressive agenda during the ensuing negotiations. For instance, the two countries’ shared concern about the environment and interest in green technology may well become a part of their trade agreement.

François-Philippe Champagne, Canada’s minister of international trade, said that “Canada’s progressive trade agenda is in line with the government’s vision for more innovative and prosperous growth that benefits everyone.” The reality is that any trade agreement will create winners and losers. While some Canadian economic sectors will have much to gain from greater access to the Chinese market, others will pay a price because of greater competition from China. It is important for the government to be forthcoming with the public on the costs and benefits of trade liberalization and to be prepared to use policy tools to compensate those who stand to lose.

— Hongying Wang, CIGI Senior Fellow

Canadian Brand at Risk

As an American, I’m surprised that Canada wants to be the first industrialized country to bring a trade agreement with China into effect. Canada is ranked positively for quality of life and holds clout because it invests in its citizens’ education and health care, is politically stable and has relatively low levels of corruption and income inequality. The Canadian brand, in short, is to be one of a few countries that provide resources and opportunities for all people regardless of where they were born and what they believe. That brand is valuable.

Is it worth using this clout to engage in a trade relationship with China?

Sure, Canada wants to diversify its market away from the United States and could benefit from preferential access to many sectors. But China has a lot of leverage and would never agree to Canada’s progressive trade agenda, which is a major part of that Canadian brand.

Should the government continue to pursue this path, Canada could end up with an agreement that bolsters trade by providing preferential access but in no way reflects the progressive values recently put forward.

— Susan Ariel Aaronson, CIGI Senior Fellow