he pandemic has made it clear, in a deeply visceral way, that our lives are inextricably connected. Success in this networked and globalized world depends on appreciating this interconnectedness.

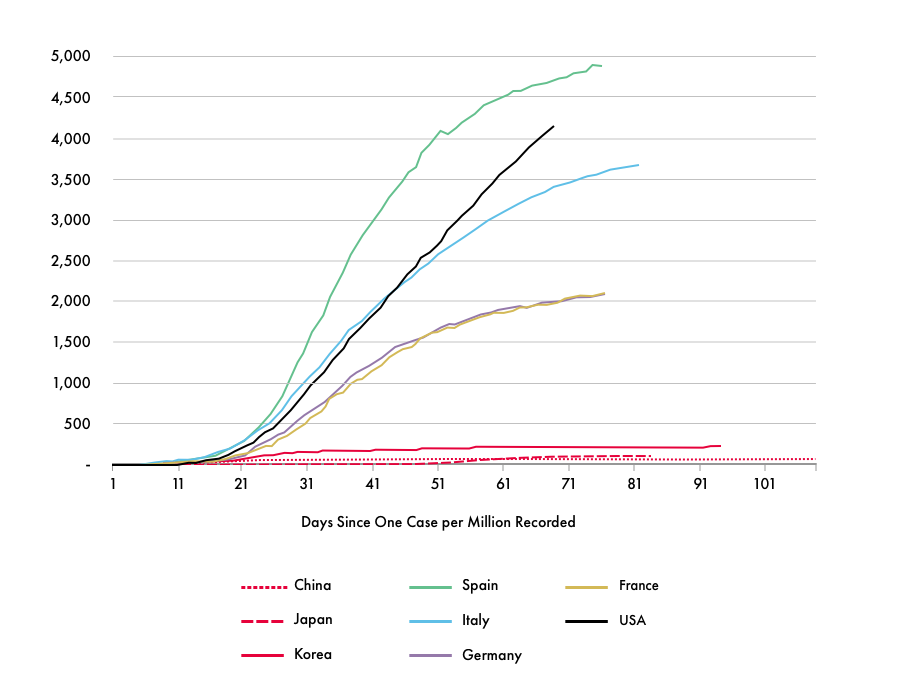

The willingness of people living in Asia to wear face masks displays an appreciation of how interconnected we are. Their success in limiting the spread of the virus illustrates the value of behaving in a way that takes others into consideration. Figure 1 shows the trend in COVID-19 infection rates in eight countries, expressed in cumulative infections per million people. There are myriad factors at play here, but it is striking how much flatter the curves are for the mask-wearing Asian countries than for the four European countries and the United States. Moreover, these Asian countries have been able to achieve much lower infection rates without resorting to the disruptive national lockdown measures used elsewhere.

Figure 1: Cumulative Cases per Million People

The advice given by public health officials in the West focused on protecting one’s self: if you are healthy, you only need wear a mask if you are taking care of an infected person. Apparently, this is still the view promoted by the World Health Organization (WHO).

But the benefit of wearing a mask does not simply lie in protecting one’s self. Its true value is found in protecting others. Since the virus may not show symptoms for up to two weeks, we don’t know who is healthy and who is sick. If everyone wears masks, we protect each other and keep infection low. This is what economists call the “positive equilibrium.”

I have heard stories of people in Western countries being stigmatized for wearing masks. In these countries, people assume that if you wear a mask, you must be sick, and you should be at home. This leads to masks not being worn and a higher rate of infection — what economists call the “negative equilibrium.” Public health authorities have a role to play in changing mindsets and promoting better equilibria. They should acknowledge our interconnectedness and encourage us to take responsibility for each other by wearing masks.

How heavy-handed should this encouragement be? In Mainland China, it is mandatory to wear masks. In the Czech Republic and Slovakia, the first two European countries to make masks compulsory, infection rates are one-third and one-eighth of Germany’s. In Japan and Korea, wearing masks is common practice; no encouragement is needed. In Hong Kong, the public’s understanding of interconnectedness exceeded that of the government, which followed WHO’s guidelines. Hong Kongers spontaneously adopted near-universal masking on their own, and health officials openly credited such public-minded behaviour for limiting the spread of the disease.

There are those who believe that being compelled to wear a mask is an infringement of their civil liberties. But the experience with masks shows that civil liberties need to be recalibrated in an interconnected world to avoid negative equilibria.

The tension between protecting individual rights and respecting the common good is also seen in the varying degrees of comfort that people express regarding using technology to track the virus’s spread.

As a Chinese resident, I have a “health QR code” on my cellphone. This scannable matrix barcode contains my passport information, my photo and my travel history, which it collects from my purchase of rail and airline tickets and my cellphone usage. Security at public places can ask to see my code before admitting me. Since I have stayed in Shanghai and have not had contact with infected people, my code is green. If I travel to less healthy areas, or have contact with sick people, my code will turn yellow or red, and I will have to isolate myself for seven or 14 days and report my condition to the public health authorities. The system is somewhat opaque and involves a loss of privacy, but it allowed the authorities to isolate the sick and made a city-wide lockdown unnecessary. To me, it seems like a positive equilibrium.

Korea is using a different approach. The Korean public health authorities track newly infected people via closed-circuit television footage and geolocation data from their cellphones. Local governments are required to send emergency public alerts, disclosing where these people have been. Survey data suggests that Koreans understand the trade-offs between privacy and public health and accept these infringements on their civil liberties.

Countries are as interconnected as individuals. An emphasis on autonomy risks our descent into negative equilibria. For example, in April, President Donald Trump ordered the medical device manufacturer 3M to stop exporting N95 masks, critically needed personal protective gear for medical workers, to Canada and Latin America. But the United States’ and Canada’s health-care supply chains are deeply intertwined: nurses from Windsor, Ontario, travel to Detroit, Michigan, each day to care for the sick, and 3M uses Canadian paper to make its masks. Retaliation by Canada could have precipitated a downward spiral in which both Americans and Canadians would have suffered from even fewer health-care resources. Fortunately, 3M announced a plan to expand imports from its Chinese plants, which will allow it to continue sending its US-made masks to Canada and Latin America, where the company is the primary source of supply.

Similarly, one wonders what measures to insulate supply chains from shocks can really accomplish. The Japanese government is providing the equivalent of US$2 billion in loans to support firms in relocating their operations from China to Japan. According to The Japan Times, the government is worried about supply-chain disruptions in China hurting Japanese manufacturers. But there are problems with this approach: the loan program is relatively small, Chinese demand is likely to continue to act as a magnet for Japanese investment and unfavourable demographics make it challenging for Japanese firms to return home. No place on earth is immune from an act of God that could potentially undermine supply chains. Indeed, Japanese supply chains were hard hit by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. Ultimately, open borders and a nimble global supply response may be the best disaster-management plan.

While some may be uncomfortable with the notion that we are not independent, there are clearly benefits to taking a broader view. Recent research shows that individualistic societies have been less effective in reducing the movement of people to curb the spread of COVID-19. If, like those in Hong Kong, we can acknowledge the extent to which we affect one another, we can avoid negative equilibria and increase our chances for success in this highly interconnected world.