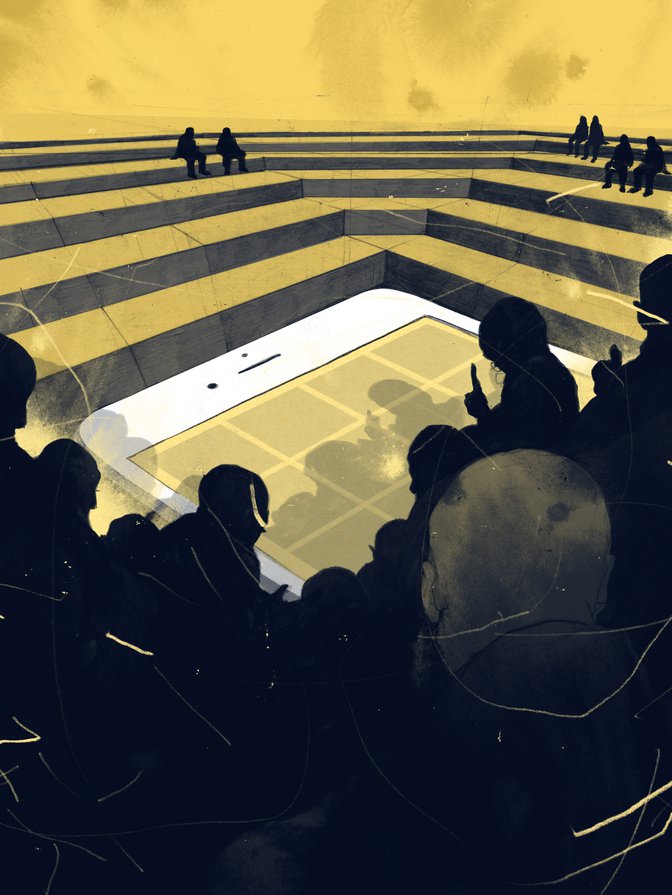

handful of dominant platform companies that combine data gathering, media distribution and advertising now have immense power to affect our actions. By processing our personal data and monopolizing our attention, companies such as Facebook and Google can deploy artificial intelligence (AI) to optimize and target messages to us based on sophisticated profiles of our weaknesses, wants and means. In short, having our attention and data enables them to modify our behaviour — from purchasing decisions, to dating, to voting. With this power comes responsibility — to work for the public interest rather than against, and to deal with the negative outcomes that such activities can create.

Power also needs checks and balances. Countries around the world are working toward a new “settlement” on the rights and responsibilities of platforms. This settlement is not just about punitive laws. It will look at the responsibilities of the platforms themselves to protect their users and whether existing businesses have any incentives to deal with the social problems they may be associated with, as well as consider how the law will provide the right incentives to curb online harm without overbearing regulation.

Dangers of Speech Control

Economists often refer to pollution as an example of a negative externality — that is, an unintended impact of business, with undesired or damaging effects on people not directly involved. Policy makers across the political spectrum agree that digital platforms’ engagement-driven business models are polluting the public realm with harmful, hateful, misleading and anti-social speech and other externalities. Self-regulation by companies such as Facebook and YouTube is seen as ineffective, and there is now a consensus in favour of more formal and transparent regulation by independent regulators or courts. From the point of view of free speech, such a consensus is dangerous. Censorship and chilling of free speech is a constant danger when considering governance of such platforms.

Even before this new regulatory mood, North American commentators looked to Europe to solve the problems that arose with the phenomenal success of US platform companies. The European Commission has levied eye-catching antitrust fines,1 and in 2018 passed the General Data Protection Regulation, which rapidly became the standard for the world. The hope is that as a continent with a reputation for effective regulation and strong protection of free speech, Europe will also provide the answer for online harm.

Censorship and chilling of free speech is a constant danger when considering governance of such platforms.

Most recent European reforms have taken place at the member-state level. The United Kingdom and France have each published legislative proposals for social media regulation and Germany passed the Network Enforcement Act in 2017.2 Such policies have in common an attempt to tighten the liability obligations on online intermediaries to ensure that they have strong incentives — including fines — to deal with harmful content and conduct more promptly and effectively, and reduce its prevalence online.

European Commission activity to date has focused mainly on encouraging self-regulation: corralling platforms to observe conduct guidelines on hate speech, misinformation and terrorism, without major change to legislation. The overall policy settlement established in the 1990s — under which platforms were immune from liability for hosting illegal content until notified of it, and free to develop their own rules for content that is harmful but not illegal — remains intact, although the European Commission has published more guidance on how platforms can deal with socially questionable content.3

Alongside the debate about illegal and harmful content, proposals have been developed to update competition and fiscal policy. Multiple European countries have implemented or made proposals for new taxes on digital platforms. The proposed “digital services tax” in the United Kingdom, for example, would be calculated as a percentage of advertising revenue in the United Kingdom. Competition regulators are looking into what new forms of antitrust are necessary to deal with multi-sided data and advertising markets. The next phase is the difficult part: coming up with pan-European rules in areas that require it, standardizing this thicket of new regulation, yet enabling national policies and forms of accountability where citizens expect them. It is inevitable that such policy developments will eventually come into conflict with the existing European legal settlement on online intermediaries, namely the directive on electronic commerce.4

Challenges and Contradictions

As a policy area that has implications for economic development, competition, free speech, national security, democracy, sovereignty and the future role of AI, we should not expect the negotiation of a new regulatory settlement to be simple. The initial phase in this policy cycle has revealed the following challenges and contradictions, among others.

The need for subsidiarity and accountability of standard setting, but also the pressures for regional and global standards of procedure on efficiency grounds: Sensitive issues of media policy and democratic accountability — such as those raised by, for example, the Cambridge Analytica scandal and so-called disinformation — are best resolved close to consumers in a transparent fashion. For issues such as speech considered to be insulting, threatening or even inciting violence, context and culture are paramount. Any new law on speech or definition of harmful speech will be instantly controversial, and rightly subject to calls for transparency, subsidiarity, due process and open accountability. The balance between law and self-regulation will, inevitably, be difficult to strike: platform self-monitoring schemes are often seen as preferable in that they invest power in the users themselves, but such systems have been criticized as ineffective in hindering hatred and misinformation online. In this context, the present period is characterized by struggle between platforms, parliaments and the European institutions over who sets the rules of speech. Whatever new standards and norms for speech are involved, it is clear they will be multi-levelled, in line with other European rules on speech, such as the Audiovisual Media Services Directive.5 At some point, efficiency will dictate a Europe-wide baseline of legal standards of acceptable speech, and a layer of opt-in standards that vary by company or platform.

Controversies about who is responsible for protecting whose free speech: As platforms are ever more called upon to regulate speech to prevent negative outcomes, they are inevitably criticized as unaccountable private censors. European and international standards on freedom of expression are increasingly held up as relevant to these “censorship” activities of platforms,6 but there is uncertainty about what duties states have to regulate platforms to ensure they protect free speech of users.7 As fundamental rights are asserted online, the focus of activity has been to protect rights other than free expression — such as privacy8 — but assertion of platform regulation will inevitably conflict with speech rights. The United Kingdom’s Online Harms White Paper has been criticized, for example, for undermining the European Court of Human Rights principle that restrictions on free expression need to be “enshrined in law” (and therefore subject to parliamentary and public scrutiny) rather than hidden somewhere in standards developed in the shadowy space between platforms and government.9 There will be a need for clear, positive assertion of rights and obligations of users, platforms and governments, and these are not provided by current standards.

Assertion of platform regulation will inevitably conflict with speech rights.

The need to bring together disparate policy instruments into a coherent overall framework and regulatory architecture: In the United Kingdom, and other European countries, internet intermediaries face parallel policy processes in the areas of taxation, competition and content regulation. It is inevitable that these discussions will be brought together on grounds of regulatory efficiency. There are concrete attempts at the national and European level to redefine competition policy: there is a consensus that competition law has failed in the light of platform business models to check new forms of market power, such as dominance of data in complex multi-sided markets. Yet competition proposals, such as the Furman Review,10 and current proposals for fiscal reform, such as the digital services tax, have no social component: they do not attempt to use fiscal policy to alter incentives for companies to mitigate negative social externalities. Although it is true that there may be freedom of expression concerns with such a foray into the speech field, sooner or later the role of these fiscal levers will come into play, particularly if the public purse benefits from the business models of the tech giants, while doing nothing to shape their behaviour. In the old world of broadcasting, specialist regulators such as the UK Office of Communications dealt with matters both of competition and social regulation. It is likely that regulators — perhaps the same ones — will do the same with social media platforms.

Fiscal, market structure and competition issues entangled with issues of fundamental rights, media accountability and responsibility: It would be hard to sustain the claim that a small social media platform prohibiting or removing a post is a “censor” of speech or that, with its handful of subscribers, it could have a profound effect on the right to impart and receive ideas in the way that Facebook or Google would. A political viewpoint or an artistic expression that breached Facebook’s guidelines on extremism and hate, or even one that failed to meet a threshold for “trusted” or “quality” journalism on YouTube, could be consigned to the sidelines or even silenced. So, competition law and regulation, as they have done in the past in relation to media pluralism, will in some sense combine general social interests and matters of special public interest in new ways through behavioural competition policy and also merger rules. Law makers can have a profound influence on how the digital media business model develops. The key question is the division of labour between European and nation-state regulators.

The limitations of platform regulation in preventing online harms will also have to be faced.

The general problem with this flurry of policy activity is, therefore, fragmentation — at the national level between fiscal, competition and content regulation, and at the European level between separate complex nation-state-level regulatory policies, which could in time create problems for the operation of the single market. Clearly, there will be pressure to simplify and standardize across Europe: there are strong economic imperatives for a pan-European solution that would reduce platform costs in national tailoring and governance of services. Whatever the Brexit outcome, there will likely be strong imperatives for the United Kingdom to align.

Toward a New European Settlement on Platforms’ Rights and Responsibilities

It is unfortunate that such a key challenge for European governance coincided with the dual crises of the euro zone and Brexit. The response will have to be pragmatic, addressing the challenges of the current impasse with platform regulation and developing careful and creative answers for the challenges of multi-levelled governance. The European Commission’s recommendation on tackling illegal content online,11 which permits member states to require a “duty of care” by platforms on the model of the UK proposals, will need to be reviewed along with the electronic commerce directive, which offers platforms a holiday from liability, and a much more solid evidence base about consumer harms gathered at both the pan-European and member-state level. What is being attempted is a gradual “responsabilization” of platforms: by changing the incentive structures, regulation and liability will seek to encourage a new ethics of responsible platforms, which can provide certainty, fairness and accountability of enforcement of speech rules, but ensure that speech control is strictly autonomous from the state. Policy makers will use a broad tool kit to achieve the right incentives: tax breaks, distribution rules and competition policy, as well as regulation.

There are numerous challenges in this multi-levelled policy game. The first is the power of the actors involved: US companies have funded a huge lobbying exercise that attempts to deploy new notions of internet freedom to stymie calls for accountability, often using the opinion-shaping power and public reach of the platforms themselves to oppose regulation. One strong factor in the favour of progressive reform, however, is that vested interests in the legacy media can be deployed in support of policy reform. Legal reforms in Germany and the United Kingdom have enjoyed firm support from the press.

The limitations of platform regulation in preventing online harms will also have to be faced. The platforms, fortunately or unfortunately, are not the internet. Attempts to regulate them may lead to a tendency for content to migrate to other, less-regulable places on the internet. This will ensure the whole process is disciplined by consumer power. If consumers feel the rules are inappropriate or illegitimate, and if competition policy successfully creates the opportunity to switch, they will vote with their clicks and go elsewhere.

In the next policy cycle, it is inevitable that the current framework for intermediary liability will come up for scrutiny, and we may see a new understanding whereby governments and regulators are more active in monitoring self-regulation by social media and other intermediaries. But in an environment characterized by an understandable lack of faith in democratic institutions, the argument for subsidiarity in media accountability is overwhelming. Censorship, whether through the targeting or subsidy of speech by law or the opaque fiat of powerful private actors, would not be trusted. Whatever the eventual architecture of speech control, whatever the eventual settlement on the rights and duties of platforms, it must be rooted in civil society and legitimate in the eyes of users.