The environment has always been a concern for Aboriginal confederacies and nations in North America. It remains the source for knowledge systems, laws and sciences; this holds true for the nations on the prairies. For endless generations, and through many ecological crises, the dynamic webs of the ecosystem have been core to their ceremonies and sensibilities. The nations' experiences with biotic and abiotic forces shaped their knowledge system and served as their education system. Further, their movement-centred languages are expressed in symbolic and mystical terms, and reveal a patient, open-minded comprehension of the ecosystem. In order to gradually learn the complex ways of achieving a dynamic balance with the ecosystem — and to anticipate changes — nations on the prairies observed, pondered and shared their insight on and relationships with the environment.

These relationships are reflected in creation stories, songs and ceremonies, and are central to legal systems. Often, the nations viewed animals as lawgivers, lawmakers or epistemic authority. As Linda Hogan wrote in her 1995 book, Dwellings: A Spiritual History of the Living World, the nations understood their spirituality as an inseparable part of the deeper communion with the ecosystem. They comprehended that the four-legged animals that roamed the prairie represented many different intelligent spiritual energies and species. The animals and plants that they lived with generated the law that nations are to live by regarding how to relate to and care for them. The most important teacher among the four-legged animals was the bison or buffalo, whose generous covenants with the nations provided them with their spirituality and the necessities of life.

With herds once reaching tens of millions, the buffalo was the ancient farmer and bio-engineer of the ecosystem. They affected plant communities, their fur created habitats for grassland birds and insects, and they provided abundant food resources not only for people but also for species such as grizzly bears and wolves. The nations modelled their lives on the teachings learned from the buffalo’s interaction with the ecosystem.

The most important teacher among the four-legged animals was the bison or buffalo, whose generous covenants with the nations provided them with their spirituality and the necessities of life.

The knowledge system, spiritual traditions and livelihood of the nations were tied up with the buffalo. As they followed the nomadic bison over the prairie, the nations learned and pondered how every ecosystem was distinct. They learned that everything is in flux and is somehow directly connected, and that every action, no matter how small, has the potential to affect others over great distances. They learned from lightning strikes on the prairies that fire encourages early spring grass growth, which produces larger populations of buffalo. Early European explorers saw vast oceans of prairie grasses that nourished the buffalo, never suspecting that they were looking at patient, ancient landscaping established by fire. They did not comprehend that the 162 million hectares of prairie grasses had physically and spiritually nurtured the bison and the nations for millennia — they considered it as wasteland.

The nomadic newcomers had no comprehension of the prairie ecosystem of the Indigenous landscapes or the responsibilities that were associated with the knowledges. They brought to the prairies an endless terror of ecological crisis. They sought to transform the prairie into European farms and ranches. As Andrew Isenberg wrote in The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, it took only three decades to nearly exterminate 30 million bison and drive prairie nations into submission by starvation. The nations entered into treaties with the British sovereign and the United States that promised not to interfere with their hunting and harvesting economy on the transferred lands.

The immigrants sought to change the ecosystem. They divided, fenced and ploughed the grasslands, imported farming practices and livestock, replaced the indigenous grasses with European exotic grains, diverted the region’s streams, overgrazed the pastures, overused the soil and overhunted the wildlife. They discovered hidden fossils and fuels and transformed the prairies into commodities and commerce with imported property laws.

After the constitutional recognition and affirmation of Aboriginal and treaty rights in Canada, the nations began the arduous processes of restoring their damaged knowledge systems and ecosystem. The restoration of the wild buffalo was integral to their recovery.

Following the advice of Elders, Blackfoot professors Leroy Little Bear and Amethyst First Rider of the University of Lethbridge conceptualized the Buffalo Treaty and generated interest among the leaders of the InterTribal Buffalo Council. Little Bear and First Rider engaged and maintained an allied advocacy network — composed of the Wildlife Conservation Society’s Bison Conservation Program and Tribal Partnerships, the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Bison Specialist Group, the American Bison Society and Bison Belong — that was committed to repatriation of buffalo in Banff National Park and other national parks as wildlife, and developing an international grazing corridor. As a grassroots effort, assembling and coordinating this network, and negotiating and drafting the treaty took more than a decade. This innovative form of Indigenous treaty making reflects the complex relationship between diplomacy, Indigenous law, spirituality and the environment.

In 2014, the Blackfoot confederacy and allied nations initiated the continental Buffalo Treaty — titled The Buffalo: A Treaty of Cooperation, Renewal and Restoration — on the Blackfoot reservation in Montana. The treaty is a historic, inspiring, multi-faceted and living agreement. It was the first treaty among the nations in the United States and Canada in more than 150 years, since the 1855 Treaty of Fort Laramie, which adjusted the jurisdiction over buffalo hunting grounds.

The Buffalo Treaty is an agreement among the nations, federal and provincial governments, non-governmental organizations, corporations, conservation groups, researchers, and farming and ranching communities. The treaty declares its unifying vision and purpose:

"To honour, recognize, and revitalize the time immemorial relationship we have with BUFFALO to once again live among us as CREATOR intended by doing everything within our means so WE and BUFFALO will once again live together to nurture each other culturally and spiritually…so together WE can have our brother, the BUFFALO, lead us in nurturing our land, plants and other animals to once again realize THE BUFFALO WAYS for our future generations."

The treaty was viewed as an essential part of the ecological reconciliation, and an endeavour to guide the younger generation back to a path of ecological balance and to fill a major gap in their education and lives. As Little Bear stressed, the nations of the Blackfoot confederacy’s “belief system, songs, stories and ceremonies about the buffalo remained, but the buffalo were out of sight, out of mind.” The spiritual loss would be similar to removing all the church buildings from Christianity; the economic loss similar to taking grocery stores from consumers.

The treaty has been ratified by many confederacies and nations, and it has established an alliance among the Great Plains nations to restore the buffalo on reserves, reservations or co-managed lands, and to improve the grasslands. It commits the nations to ongoing dialogue and compelling advocacy for buffalo conservation, restoration and the reintroduction of buffalo to the grasslands. The treaty leaves it up to each signatory to decide how to approach buffalo and ecological restoration.

The spiritual loss would be similar to removing all the church buildings from Christianity; the economic loss similar to taking grocery stores from consumers.

The Buffalo Treaty has become a model for other nations’ relationships with the ecosystem. It has inspired similar treaties for the protection of grizzlies, salmon and moose elsewhere.

In 2017, Parks Canada, with the cooperation of the nations, reintroduced the first herd of 10 wild buffalo to the remote and fenced region of Panther River valley in Banff National Park; the buffalo are adapting successfully to the region.

While farmers, hunters and other members of the community fear the impact of the herd escaping the park, the nations have pushed back. In the Victorian treaties (1871–1899), the Queen agreed with the treaty chiefs and headmen that the treaty nations shall have the right to pursue their usual vocations of hunting, trapping and fishing throughout the tract surrendered in the treaties to the care of Canada. The chiefs agreed that Canada would protect these rights with conservation regulations against abuse by the settlers. Under the Natural Resources Transfer Act 1930, the federal and provincial governments have constitutional obligations to protect and conserve the environment of the animals through regulation.

Under section 52, article 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, the treaty nations argue that the federal and provincial law must be consistent with their treaty rights. They point out that the Supreme Court in Grassy Narrows First Nation v. Ontario made it clear to the federal and provincial governments that the treaty implementation follows the division of powers in the constitution. Moreover, the nations point out that section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects the treaty rights from the charter rights of other Canadians and limits the balancing of conflicting interests and values.

These constitutional provisions affirm the unique knowledge systems and world views of the ancestors of treaty nations. The treaty nations rely on these constitutional obligations to enforce the provinces’ commitment to ecologically restore and conserve the grassland environment of the treaty territories. The treaty nations passed resolutions calling for Alberta and Manitoba to upgrade the status of the buffalo to protected wildlife under the Wildlife Act and its listing of species at risk. In Saskatchewan, British Columbia and in federal parks, the buffalo are classified as wildlife. In Canada, since 2004, the buffalo are considered a threatened species. The United States has established a National Bison Legacy Act (2016).

The treaty nations’ relationship to the land is reiterated, clarified, supplemented and invigorated by the International Labour Organization’s 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Regrettably, Canada and the Prairie provinces have ignored, violated and abused their constitutional obligations to the treaty nations to maintain an ecological balance within the land. The provinces have failed treaty nations and settlers by using their constitutional powers to establish artificial economies and private profits, rather than for ecological conservation.

The treaty nations can no longer wait for solutions from government and corporate leaders or political parties. Based on their constitutional, global and human rights, and ecological sensibilities, they must act and take responsibility to restore a healthy relationship with the ecosystem and with each other; everyone must personally decide what the future will look like.

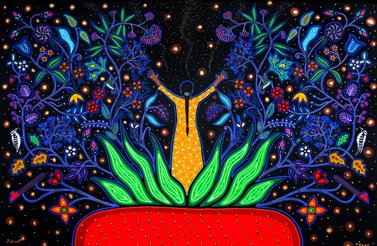

About the artist: Adrian Stimson is an interdisciplinary artist and a member of the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation. His paintings are primarily monochromatic, depicting bison in imagined landscapes. They are melancholic, memorializing and sometimes whimsical. They evoke ideas cultural fragility, resilience and nostalgia. In 2018 Adrian was awarded the Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.