In the mid-1900s, the shearing frame was introduced to automate work in the textile industries, and English workers found their skills, professional experience and, above all, their livelihood in danger. The new technology worked faster and more efficiently and produced products that otherwise required manual labour. Effectively, the new technology threatened to turn skilled textile workers into a class that could easily be replaced by anyone willing to work as a machine attendant. Faced with the existential threat of extensive unemployment and decreased wages, these English workers organized under the mystic name of “Luddites” and launched a series of attacks on the machines. In his book Breaking Things at Work, Gavin Mueller (2021) writes that Luddites saw the promise of technological efficiency for its potential to lead to violence and as a threat to their livelihood. They did not fear the technology as much as they feared how machine efficiency was about to change their world. What remains true and relevant from this story in the context of interoperability of border information systems is precisely this double bind between efficiency of the new technology and its violent remaking of the world in which it operates.

Efficiency remains the main driver of technological advances, the mantle under which a lot of promise is supposed to be realized. So, it should not be news that the European project to interoperate border surveillance data is all about effectively and efficiently overcoming shortcomings caused by the operation of dispersed and overlapping national border information systems, bridging the gaps in data management and harmonizing the complex landscape of national governance of traveller data.

The European Architecture of Traveller Data Interoperability

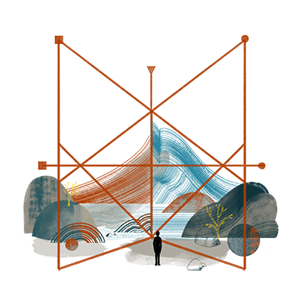

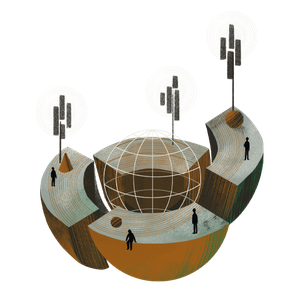

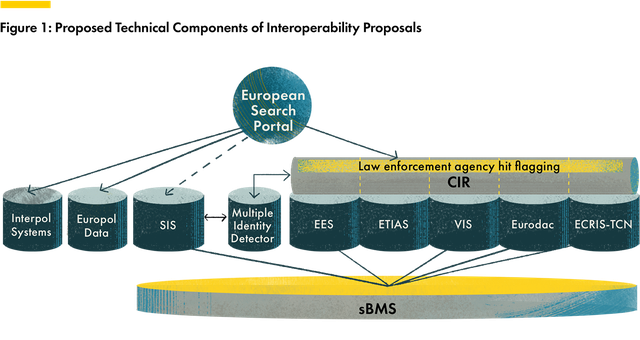

On June 11, 2019, regulations for the current European architecture of traveller data management came into force, overhauling the European border data strategy by establishing an interoperation framework for nine separate personal databases pertaining to cross-border travel across and beyond the European Union. The data in question here includes, but is not limited to, a variety of biometric information, biographical data, travel history, criminal records, identification and identity documents pertaining to the history of travellers who are of interest to European border-control authorities. This interoperation system includes the Schengen Information System (SIS), the Visa Information System (VIS), Eurodac (the European fingerprint database of asylum seekers and “irregular migrants”), the European Travel Information and Authorisation System (ETIAS), the Entry/Exit System (EES), the European Criminal Records Information System-Third Country Nationals (ECRIS-TCN), Interpol’s Stolen and Lost Travel Documents database and Travel Documents Associated with Notices database, and the Europol database (as far as it is relevant for the functioning of ETIAS) (see Figure 1).

The interoperation of such a diverse mix of authorities, types of data, competencies and legal mandates were, in turn, realized by establishing three new components in the European Union’s border data architecture: the Shared Biometric Matching Service, or sBMS, the Common Identity Repository (CIR) and multiple identity detector.

The European Commission notes the beginning of this data interoperation in 2016 and through its Communication 205: “Stronger and Smarter Information System for Borders and Security.” This temporal demarcation allows for framing the interoperability of data systems as a response to the 2015 migration of Syrian refugees as well as a number of coinciding terrorist attacks in Europe. Yet the new data architecture of European borders was already in development since 2008 under the auspices of the commission’s so-called Smart Borders Package. In such framing of its interoperation project, the European Commission claims an ex post facto justification of its move to interoperationalize border and visa information systems with those of the police and judicial entities such as Interpol and Europol. So, the interoperation of border information systems increases the efficiency of the European Union’s border authorities, while at the same time mobilizes its resources — both legal and material — from criminal and judicial apparatus as part and parcel of the migration control regime.

Interoperational World Making

Whether such an interoperable system is functional or can create a gapless border space or prevent irregular cross-border travel into Europe, is up for debate. Migration law scholar Evelien Brouwer (2019) points out that the functionality of such systems largely relies on trustworthiness of the input feeds of the users located in various nations, dealing with different institutional and bureaucratic cultures, and diverse legal competencies and obligations. There is also the question of the “situatedness of data” (Loukissas 2019). Data cannot, in any reliable manner, be generalized in such ways that separate it from its specific place, time, social relations, technological interfaces and algorithms that originally allowed for its production, collection, representation and processing.

Beyond this observation, technological tools are both manifestations of desires to overcome certain issues and representations of social life itself, as Sheila Jasanoff (2015) points out. Technological solutions are co-producing the social world as much as they are being deployed to address any given question in the world. This concept relates to the experience of the Luddites. Whereas, on the surface, the Luddites might appear as reactionary technophobic forces, in reality, what they were fighting and resisting was the social world of increasing unemployment, devaluation of skilled labour and decreased social security that the automating of their tasks created. So, with regard to border-control technologies, beyond questions of trustworthiness, reliability or even conformity with fundamental rights, we must include examination of the world of mobility and travel that such technologies help create.

On the surface, the European interoperation of border, police and judicial information systems increases European border security by efficiently flagging visa overstayers, high-risk travellers and identity fraud cases, and preventing irregular cross-border travel. However, the exclusionary impulses of these technologies produce a world in which travellers who seek protection or a better livelihood are forced to take higher risks, travel increasingly dangerous terrains and have their own body — in the form of its machine-readable data — weaponized against themselves.

The world of interoperable border information systems is also the world of harraga (Arabic for “those who burn”) — those who destroy any trace of their identity, not just their identity documents but also their fingertips with acid, fire or razors in order to avoid biometric readability. The world of impenetrable and interoperable borders is also the world of mobility in which migrants die of hypothermia in refrigerated trucks that travel across borders monitored by artificial intelligence-enhanced thermal cameras. It is also the world of suffocation under cargo travelling across borders that is monitored by carbon dioxide detectors that trace human breathing. This world of mobility is part and parcel of the same world of mobility made efficient through interoperability of data platforms and must irreducibly be treated as such and as a whole.

That said, the author wishes to end this essay not with a closure but with an opening. This opening concerns the Luddites’ strategy of breaking machines on the one hand and the idea of interoperation on the other. In simple terms, interoperability can be defined as an act of pooling all of our resources under a holistic vision for creating an ever more effective and efficient operation. By turning interoperation on its head and refusing to treat it as an exclusive prerogative of the illegible tech class, we can mobilize this term to mean the progressive act of “reconfiguring everything we have in order to address everything we need to secure a safe, equal and fair life for all” — that, in a nutshell, is in the words of Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2020) the politics and practice of abolition of all that makes our lives vulnerable to violence.