Historically, there has been a clear distinction between civilian and military space equipment. In recent years, the majority of space equipment, such as communications and Earth-observation satellites, was launched and operated by the private sector. This private sector equipment is being used by both civilian and military groups and is referred to as “dual use.” In an era of increasing cyberattacks, space-based equipment that provides both civilian and military services is coming under attack. A foreign adversary, hacktivist or terrorist may target the military activities of a particular satellite, possibly creating unintended consequences for civilians using the same equipment. For example, attacking a communications satellite could interfere with military communications as intended, but also disable internet access in remote regions that rely on it for telemedicine or banking. This could put civilians in harm’s way.

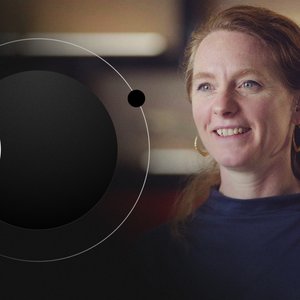

In this video, Cassandra Steer, deputy director of the Australian National University Institute for Space, explains how international humanitarian law (IHL) protects civilians from the horrors of war. While the most recent Geneva Conventions were formed after the Second World War, long before satellites and the internet existed, the treaties extend to all future forms of warfare, meaning that the civilian is to be protected from any warfare activities conducted on cyber and space systems.

Cyberattacks often fall below the threshold of full-scale warfare into what is known as the “grey zone,” making it difficult to determine if an escalatory response is necessary. An added complication is the dual-use nature of space-based systems: “It is increasingly difficult to identify which assets are civilian and which are military, especially when the majority of satellites are commercially owned and providing services for both military and civilian groups,” explains Steer. Ultimately, IHL errs on the side of protecting the civilian. To reduce future potential impacts on civilians who rely on space and cyber systems, law makers need to further define how IHL applies to dual-use assets.