The accelerating exploitation of Earth’s near-space realm, in particular for telecommunications, navigational systems and low-Earth orbit monitoring, has generated two significant phenomena for the conduct of global geopolitics. One is a dawning recognition that space systems now constitute vulnerable critical infrastructure (CI) for states and societies. The other is a realization that private sector activity in space has generated a profound change, with space-based private sector assets playing a major role in the creation of an array of dual-use technologies in space, in particular with regard to Earth observation. These developments have added to the extant national security significance of space as an arena for intelligence gathering from imagery satellites, dating back to the US deployment of the first generation of Corona spy satellites in the 1960s.

The growing danger to important space assets has become a persistent theme of Western national security threat assessments. In February 2022, on the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the US intelligence community released its annual worldwide threat assessment for 2022. It called attention to offensive counterspace capabilities being developed by both China and Russia. The assessment noted that “Russia is investing in electronic warfare and directed energy weapons to counter western on-orbit assets. These systems work by disrupting or disabling adversary C4ISR [command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance] capabilities and by disrupting GPS, tactical and satellite communications, and radars” (Office of the Director of National Intelligence 2022).

This reporting was followed by a more direct warning issued by the US Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), in combination with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), on March 17, 2022, focused on possible threats to US and international satellite communications (SATCOM) networks. The warning was issued in the wake of evidence about a Russian attack, just an hour before the launch of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, on the US-owned Viasat commercial SATCOM network that served Ukraine and eastern Europe. The Viasat hack, which disabled modems serving the Viasat network, including ones used by Ukrainian government agencies, was later publicly attributed to the Russian military intelligence agency, the GRU, by the US, UK and EU authorities (Schaffer 2022). In its March 2022 cybersecurity advisory, CISA and the FBI urged private SATCOM network owners and operators to strengthen mitigation measures and to “significantly lower their threshold for reporting and sharing malicious cyber activity” (CISA 2022). Enhanced reporting, if achieved, would allow CISA, which runs a 24/7 operations centre, and the FBI to gain better situational awareness and share further advisories with the private sector.

The Five Eyes partnership has already created a foundation for common multinational space operations, drawing on the US-led Combined Space Operations Center (CSpOC). The history of the centre, which dates back to 2005 as a means to control US joint military space assets, has increasingly emphasized the importance of coordination between the United States and key allies as well as between military and civil space organizations. The CSpOC has, since 2018, been reoriented as a strategic defence partnership with the Five Eyes countries at its core but with additional participation by France and Germany (US Space Command 2019). Both France and Germany operate national intelligence satellites (Abbany 2020). Germany is currently replacing its older array of SAR (synthetic aperture radar) satellites while France is unique among EU countries in operating electro-optical satellites as well as signals intelligence (SIGINT) satellites (Pons 2022).

Among the elements of the CSpOC is a unique “commercial integration cell” to allow for greater engagement with private sector satellite owners and operators (Magnuson 2022).

Concerns about the cybersecurity of satellite systems were not, of course, restricted to the US government and its intelligence agencies. It has become an issue for the long-established intelligence partnership known as the Five Eyes, which links Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. While only the United States, among the Five Eyes partners, currently deploys national satellite capabilities dedicated solely to intelligence gathering, all the countries involved have a shared interest in exploiting pooled intelligence resources derived from space-based imagery, including commercial systems, and protecting space assets, including military communications systems, from adversarial threats, especially cyberattacks.

The United Kingdom, a key partner in the Five Eyes, laid out the importance of international alliances in its recent Defence Space Strategy, issued in February 2022 (UK Ministry of Defence 2021). It highlighted UK alliance contributions, including in intelligence analysis, and noted continued close engagement with Five Eyes partners on all aspects of space strategy. The UK strategy also committed the country to develop within the Five Eyes partnership an integrated system for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance as well as the contribution of UK satellites with advanced sensor capabilities by 2025. This commitment would be in addition to the current fleet of military communications satellites operated by the UK Ministry of Defence, known as Skynet.

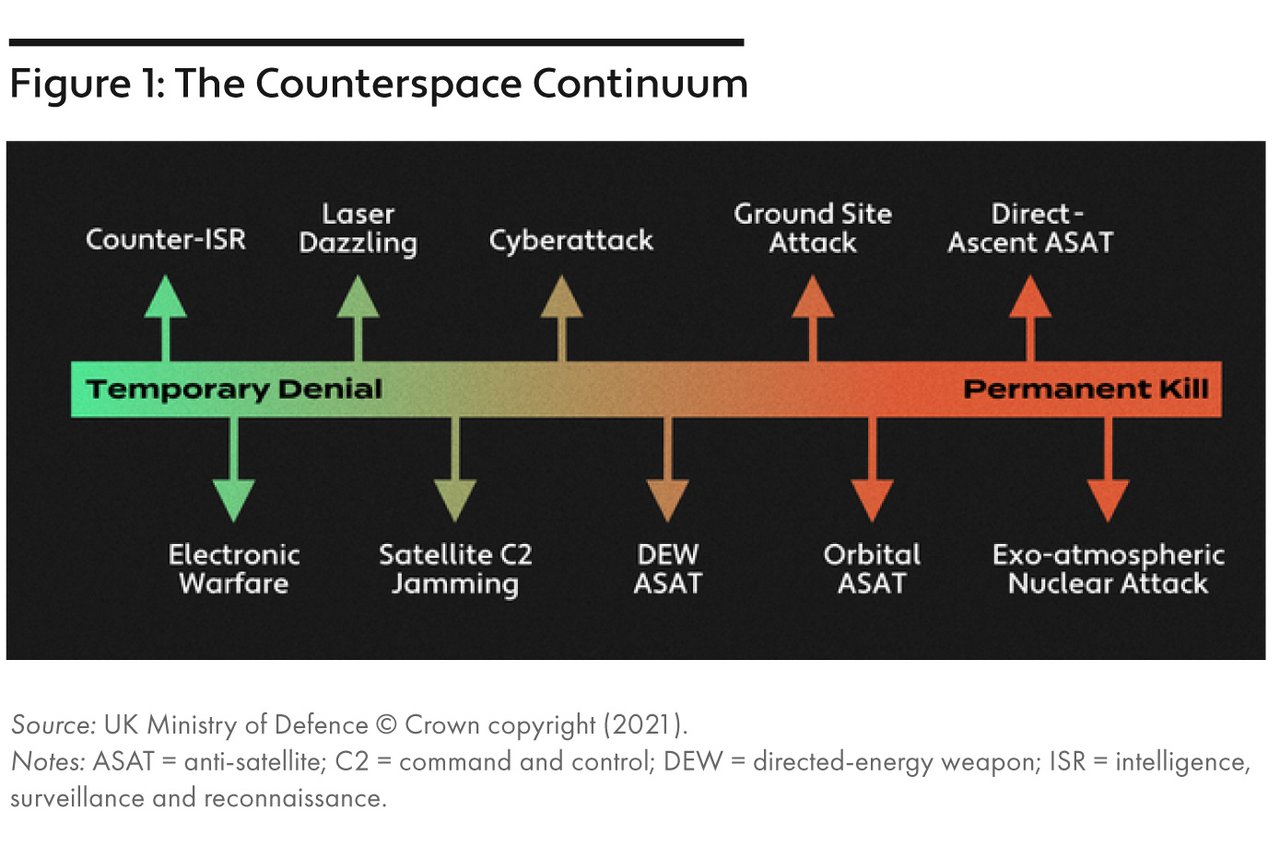

The discussion in the UK space strategy paper highlighted a range of potential threats to space CI (see

Figure 1) but called particular attention to cyberthreats and the sovereign risks for the United Kingdom of inaction in what was described as a “congested and contested” environment. In a manner similar to the US worldwide threat assessment, the United Kingdom pointed in particular to Russia and China as adversarial actors with growing counterspace capabilities.

In early 2022, Combined Space Operations participants signed a “Strategic Vision 2031” memorandum of understanding, focused on a multinational defence of space assets against hostile space activities, “in accordance with applicable international law.” The vision statement has multiple objectives but at its heart are the creation of a resilient space infrastructure able to withstand cyberthreats and other malicious interference and the enhancement of intelligence sharing from space assets (Combined Space Operations 2022). The Strategic Vision document builds on Operation Olympic Defender, initially the US military’s plan to protect and defend satellites in space. Olympic Defender was opened up to allied participation in 2018, with the United Kingdom the first country to join. Canada joined in March 2019 and has a small contingent of military personnel working at the CSpOC. Participant countries in Olympic Defender are able to bring national caveats on activities to bear as required, something considered important in weighing the development of offensive space capabilities (Hitchens 2020).

Olympic Defender also contains a component devoted to monitoring the increasing hazard of space debris. Here Canada makes a direct on-orbit contribution through its Sapphire satellite, which was launched in 2013 and functions within the US Space Surveillance Network. The Sapphire satellite was developed, built and is operated on behalf of the Department of National Defence (DND) by the private sector company MDA and is reportedly able to collect “data on more than 12,000 man-made space objects per month” (MDA 2015). To date, Sapphire represents the only contribution from a Five Eyes partner, but it is an aging asset. DND currently is running a project to replace the original Sapphire satellite (“Surveillance of Space 2”) but on an extended timeline that does not call for delivery of a new capability until the end of the 2020s, with the likely risk that the original satellite will no longer be functional by the time its replacement is on orbit.1

Efforts to defend critical space infrastructure are no longer focused purely on national security assets for imagery, signals intelligence and military communications and navigation, but of necessity encompass commercial activities in space. By one estimate, satellites serving national security and military purposes account for only about 20 percent of all active satellites.2 The other 80 percent consist of a multitude of Earth observation satellites; navigational arrays, such as the 31 satellites that comprise the US-operated GPS; and large constellations of internet satellites, such as SpaceX’s Starlink system. Officials from the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence have acknowledged that, for all intents and purposes, space assets are CI (Magnuson 2022). But many national approaches to defining CI remain earthbound.

In the US case, the Department of Homeland Security lists 16 CI sectors deemed “so vital to the United States that their incapacitation or destruction would have a debilitating effect on security, national economic security, national public health or safety, or any combination thereof” (ibid.). Space systems are not included. Two of the United States’ Five Eyes partners, Australia and the United Kingdom, do include space as a CI sector. Canada and New Zealand as yet do not, although Canada’s 2009 National Strategy for Critical Infrastructure is currently being updated. In the Canadian case, a government discussion paper on modernizing the CI strategy calls attention to a new range of threats, including those posed by digitization of systems and processes, which have expanded the attack surface for cyberthreats; environmental risks posed by climate change impacts; and persistent and new security threats, including the blockages of border CI, which were a feature of public protests in early 2022 and to which the federal government responded by declaring a public order emergency under the never before used Emergencies Act. The discussion paper calls specific attention to space as a potential new CI sector (Government of Canada 2022).

Updating CI strategies by including space systems could have important impacts. Identifying key space systems as vital CI could call greater attention to threats to their resilience and operation, especially cyberthreats; could help prioritize mitigation resources; and could lead to regulatory regimes that might include technical standards, service standards and information-sharing requirements. Such a regulatory regime could serve to strengthen cybersecurity capabilities for private sector-operated space systems. The Canadian CI discussion paper offers one potential model drawn from New Zealand practice. In the New Zealand case, entities that supply water, electricity or telecommunications services are designated as “lifeline utility” in the Civil Defence Emergency Management Act (2002). The same is true for operators of ports and airports. Being designated a lifeline utility means that CI owners and operators must participate in the development of management plans and strategies for civil defence emergencies. It should not be considered a stretch to imagine a similar approach to specified space assets.

The issue of understanding space assets as CI comes into sharper focus as we consider the accelerating commercial exploitation of space for Earth observation and telecommunications. This represents a revolutionary shift from a space realm dominated by a handful of powers launching complex and large satellite systems primarily for intelligence-gathering purposes, to a diverse world of entrepreneurial companies able to operate space platforms on the basis of reduced launch costs, available technology and smaller, but still highly capable, satellite packages. The size range of modern commercial or non-governmental satellite systems is astonishing — everything from heavy satellites such as RADARSAT-2, weighing in excess of 1,000 kg to “cubesats” of around 1 kg. These satellites can capture optical or radar imagery as they perform Earth observation missions, themselves of remarkable diversity. Their capabilities, as well as marketplace dynamics, mean that Earth observation satellites can perform as dual-use technologies, with bespoke imagery available for hire to governments that may use it to augment other intelligence sources for national security purposes.

The Ukraine minister’s appeal ended by saying, “Ukraine and the whole world will highly appreciate your contribution to peace and freedom.”

The dual-use capabilities of commercial satellite systems have been vividly demonstrated in the Ukraine war, with Western media organizations, non-governmental organizations, conflict analysts and governments all turning to them for insights into the destruction wrought by the war, the ever-fluctuating military balance and even the perpetration of war crimes. The Ukrainian government made a direct and emotive appeal to Earth observation companies in Western countries just six days into the Russian invasion. It urged companies to help Ukraine by providing high-resolution satellite imagery (especially from radar satellites, known as SAR) in real time, so that the Ukrainian military could take advantage of this intelligence source. The Ukraine minister’s appeal ended by saying, “Ukraine and the whole world will highly appreciate your contribution to peace and freedom” (Wark 2022).

While there was no public Russian response to this appeal, Russia has no similar access to private sector satellite imagery and its national satellite intelligence capabilities are far more limited than those of its Western counterparts, likely adding one more debilitating feature to the Russian conduct of the war in Ukraine to date (Krutov and Dobrynin 2022). It was against this backdrop of limited space imagery and SIGINT capabilities that Dmitry Rogozin, the then-head of Russia’s civilian space agency, Roscosmos, issued a warning that any cyberattacks on the country’s satellites would be considered a cause for war (Bender 2022). This followed claims by a hacking group that it had shut down servers utilized by Roscosmos for its satellite monitoring system, a claim denied by Russian officials.

The Ukraine war and the profound fissuring of the global international order sets the stage for future space security initiatives by the Five Eyes. The Five Eyes have demonstrated an appetite for taking public stands on shared security concerns, including with regard to cybersecurity. On the last occasion when Canada hosted the Five Eyes Ministerial meetings, in 2017, the joint communiqué addressed the “WannaCry” ransomware attack and noted “the robust cooperation underway between our five countries on cyber issues and our collective effort to study and assess key emerging issues and trends in cyber security to prevent, detect and respond to cyber threats” (Five Country Ministerial 2017). Space security may be the next logical frontier for the Five Eyes as it expands beyond its origins in the early Cold War as a pure intelligence-sharing partnership toward a geopolitical alliance. That trajectory remains in its early days but has been underscored by initiatives such as a joint declaration in late 2021 regarding their “grave concern over the erosion of democratic elements” of Hong Kong’s electoral system (Blinken 2021), which generated, in turn, a predictable and furious response from China. More recently, Five Eyes ministers met virtually in February 2022, under the chair of the UK Home Secretary, to discuss the Ukraine situation and announced a determination to continue cooperation on cyber defence and to counter disinformation (UK Home Office 2022).

The Five Eyes possesses a strong foundation for collective action on space and cybersecurity in the US-led, multinational CSpOC. The challenge for the future will rest in whether the Five Eyes members can generate a collective policy not just on threats to space and cybersecurity, but on appropriate mitigation strategies. This will test the common bonds of the Five Eyes members in terms of their national outlooks on cybersecurity standards for space operations and pre-emptive policies to deal with threats to CI in space. It will also test the ability of the Five Eyes to collectively advance partnerships between government and the private sector space industry. For the moment, the Five Eyes test will rest on the national space strategies adopted by the individual members of the partnership. The extent to which they describe a shared strategic vision for space and cybersecurity will be the best indication of the likely way forward for the Five Eyes. The United States, the United Kingdom and Australia all have recently published dedicated space security strategies. Canada and New Zealand are laggards, although both have devoted policy attention to this issue. A larger unknown is the extent to which a future collective Five Eyes strategic policy on space and cybersecurity, advanced in public, might contribute to an enhancement of global approaches to space security, or mark a further fracturing of efforts to establish international norms and laws.